"CRAZY PICTURES"

The beginnings of Manga in Japanese Art

Saturday, 15.02.03

Saturday, 02.08.03

More info:

046030800he term "manga" - "occasional paintings" - was first used in the 19th century. Since the manga, drawn freely and directly onto the page, are sketches full of humour, the term has been applied to comic works. They include satirical pictures and caricatures of the elite, of religious figures, samurai, actors, deities and other personages.

The earliest and most renowned caricatures found in Japan were apparently drawn by carpenters on the ceiling boards in the main building (Kondo) of the Horyuji Temple, constructed in Nara during the 7th century. Amusing caricatures have also been found on the plinths of statues of Brahma and Indra in the Toshodaiji Temple, built in Nara in the 8th century. These sketches are comic representations apparently intended to ward off evil spirits. This implies that a tradition of humorous painting is common both to belief and to religion. In the 8th century Shosoin, the repository of the Todaiji Temple at Nara, comic paintings have been found, including funny faces with grotesque expressions and eyes cut out of the fabric (fusakumen). A document found there, dated to 745 CE, has, in one corner, a caricature of a bearded man with his eyes bulging out of their sockets (daidairon).

In the Phoenix Hall of the Byodoin Temple at Uji, with its characteristically Heian (794-1185) architecture, there are caricatures of the junior officials of the court. At that time, creating funny pictures (oko-e) was a popular pastime among the nobility. Towards the end of the period, a scroll of caricatures appeared, known as the "Scroll of frolicking creatures" (Choju giga), or the "Scroll of frolicking people and animals" (Choju jimbutsu giga), usually attributed to the Buddhist monk Toba Sojo (1053-1140). In this scroll, considered as one of the finest examples of Japanese comic art, satirical drawings depict animals as humans. Monkeys, hares, birds and frogs appear as priests or aristocrats busily playing competitive games - representing their aspirations to political power. There is also a monkey in the guise of a Buddhist monk who is praying to a statue of a Frog-Buddha enthroned on a lotus.

Over the years the expression "Toba-e" (Toba paintings) was used for the genre of Japanese comic pictures. Typically, these consisted of grotesque figures with greatly exaggerated limbs. In two other scrolls from the same period - "Tales from Mount Shigi" (Shigisan engi emaki), and the "Ban Dainagon ekotoba" - there are comic elements and exaggerated, grotesque depictions of people.

As Buddhism spread in the Kamakura era (1185-1333), illustrated scrolls were created, based on the Buddhist beliefs in hell and human suffering. They contain scenes of hell (Jigoku-zoshi), hungry spirits (Gaki-zoshi), and various diseases (Yamai no soshi).

The belief that demons appear on specific nights and vanish with the dawn was already prevalent in the Heian period, but it was only in the 14th century that a scroll appeared depicting the Night Procession of One Hundred Demons" (Hyakki Yagyo). Such pictures were painted under the influence of the folk beliefs prevalent in a time when war succeeded war. There can be no doubt that these scrolls depicted subjects that frightened the people of that time, but the great imagination and the daring, grotesque sketches, while frightening, nonetheless bring a smile to the lips of the viewer. From the onset of the Edo period (Edo: 1603-1868) such subjects were represented humorously, with no religious connotations. This is evident in the works of Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) in the exhibition.

Many of the ink paintings made by the Zen monks have a comic aspect. These paintings, usually made with quick, spontaneous brushstrokes, portray famous Zen masters and monks, and even caricatures of saints or deities. They have no symbolic religious meaning. In the comic Zen-style paintings of Nakai Ranko (1766-1830) and Kano Isen (1775-1828), there are humorous representations of Hotei, the god of happiness and Daikoku, the god of wealth, two of the seven gods of good luck.

With the rise of a popular culture in the Edo period, comic and genre paintings appeared (Fuzokuga: pictures of daily life). Funny paintings, known as "Otsu-e" (pictures from Otsu), appeared at the beginning of the Kanei period (Kanei: 1624-1644), and were sold as mementos to pilgrims visiting the Miidera Temple in Otsu, and to travellers on the Tokaido Road between Edo and Kyoto. Most of these paintings, and their subject matter - comic references to demons and to the conduct of the monks - represent folk art in all its naive humour. For example, a demon disguised as a wandering Buddhist monk bangs a gong on his chest and begs for alms. Has the demon repented of his evil ways and become a Buddhist, or is he badgering people to give him alms for his own wicked purposes? The paintings are characterized by broad, free brushstrokes, ahe term "manga" - "occasional paintings" - was first used in the 19th century. Since the manga, drawn freely and directly onto the page, are sketches full of humour, the term has been applied to comic works. They include satirical pictures and caricatures of the elite, of religious figures, samurai, actors, deities and other personages.

The earliest and most renowned caricatures found in Japan were apparently drawn by carpenters on the ceiling boards in the main building (Kondo) of the Horyuji Temple, constructed in Nara during the 7th century. Amusing caricatures have also been found on the plinths of statues of Brahma and Indra in the Toshodaiji Temple, built in Nara in the 8th century. These sketches are comic representations apparently intended to ward off evil spirits. This implies that a tradition of humorous painting is common both to belief and to religion. In the 8th century Shosoin, the repository of the Todaiji Temple at Nara, comic paintings have been found, including funny faces with grotesque expressions and eyes cut out of the fabric (fusakumen). A document found there, dated to 745 CE, has, in one corner, a caricature of a bearded man with his eyes bulging out of their sockets (daidairon).

In the Phoenix Hall of the Byodoin Temple at Uji, with its characteristically Heian (794-1185) architecture, there are caricatures of the junior officials of the court. At that time, creating funny pictures (oko-e) was a popular pastime among the nobility. Towards the end of the period, a scroll of caricatures appeared, known as the "Scroll of frolicking creatures" (Choju giga), or the "Scroll of frolicking people and animals" (Choju jimbutsu giga), usually attributed to the Buddhist monk Toba Sojo (1053-1140). In this scroll, considered as one of the finest examples of Japanese comic art, satirical drawings depict animals as humans. Monkeys, hares, birds and frogs appear as priests or aristocrats busily playing competitive games - representing their aspirations to political power. There is also a monkey in the guise of a Buddhist monk who is praying to a statue of a Frog-Buddha enthroned on a lotus.

Over the years the expression "Toba-e" (Toba paintings) was used for the genre of Japanese comic pictures. Typically, these consisted of grotesque figures with greatly exaggerated limbs. In two other scrolls from the same period - "Tales from Mount Shigi" (Shigisan engi emaki), and the "Ban Dainagon ekotoba" - there are comic elements and exaggerated, grotesque depictions of people.

As Buddhism spread in the Kamakura era (1185-1333), illustrated scrolls were created, based on the Buddhist beliefs in hell and human suffering. They contain scenes of hell (Jigoku-zoshi), hungry spirits (Gaki-zoshi), and various diseases (Yamai no soshi).

The belief that demons appear on specific nights and vanish with the dawn was already prevalent in the Heian period, but it was only in the 14th century that a scroll appeared depicting the Night Procession of One Hundred Demons" (Hyakki Yagyo). Such pictures were painted under the influence of the folk beliefs prevalent in a time when war succeeded war. There can be no doubt that these scrolls depicted subjects that frightened the people of that time, but the great imagination and the daring, grotesque sketches, while frightening, nonetheless bring a smile to the lips of the viewer. From the onset of the Edo period (Edo: 1603-1868) such subjects were represented humorously, with no religious connotations. This is evident in the works of Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) in the exhibition.

Many of the ink paintings made by the Zen monks have a comic aspect. These paintings, usually made with quick, spontaneous brushstrokes, portray famous Zen masters and monks, and even caricatures of saints or deities. They have no symbolic religious meaning. In the comic Zen-style paintings of Nakai Ranko (1766-1830) and Kano Isen (1775-1828), there are humorous representations of Hotei, the god of happiness and Daikoku, the god of wealth, two of the seven gods of good luck.

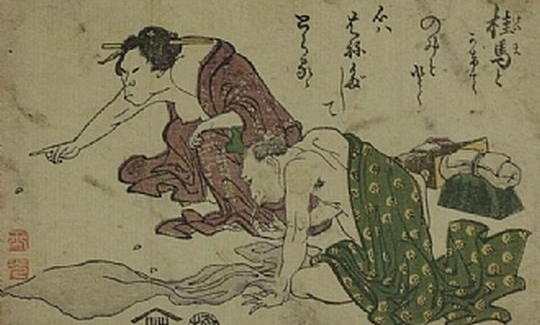

With the rise of a popular culture in the Edo period, comic and genre paintings appeared (Fuzokuga: pictures of daily life). Funny paintings, known as "Otsu-e" (pictures from Otsu), appeared at the beginning of the Kanei period (Kanei: 1624-1644), and were sold as mementos to pilgrims visiting the Miidera Temple in Otsu, and to travellers on the Tokaido Road between Edo and Kyoto. Most of these paintings, and their subject matter - comic references to demons and to the conduct of the monks - represent folk art in all its naive humour. For example, a demon disguised as a wandering Buddhist monk bangs a gong on his chest and begs for alms. Has the demon repented of his evil ways and become a Buddhist, or is he badgering people to give him alms for his own wicked purposes? The paintings are characterized by broad, free brushstrokes, and are unsigned and undated.

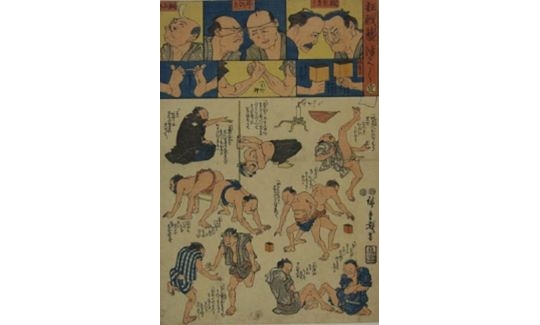

Works by some of the ukiyo-e artists (Ukiyo-e: Pictures from the Floating World) are also painted with much humour. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the woodblock prints of Toshusai Sharaku (active 1794-1795) and Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825) were caricatures of Kabuki actors with grotesque facial expressions. In 1814, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1848) published 13 volumes of sketches known as the "Hokusai Manga". Two more volumes were published after his death. Hokusai was the first to use the term ‘manga' for his series of prints of people, animals, and everything under the sun. The artist had not intended to create a series of humorous works, but they reflect the comic element in scenes of daily life. Hokusai's manga are characterized by swift, firm, free lines. On the back of his comic sketches Hokusai signed himself as "painted by a madman" (Gakyojin), or "Crazy paintings by an old man" (Gakyo Rojin). Thus, "kyoga", meaning ‘crazy paintings', was a term applied to comic paintings. Many artists, like Utagawa Toyokuni, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858) had a special signature for their humorous prints, for instance "Hiroshige giga" or "Hiroshige gihitsu" - i.e. "Hiroshige's caricature".

In Japan there has been a long tradition of humorous representations of political or social subjects that incorporate animals. The woodblock print by Kawanabe Kyosai, for instance, "An Elegant Picture of the Great Frog Battle", depicts a battle that was to take place between the Shogun's army and the warriors of the feudal aristocracy. The print shows the Shogun commander as a frog riding on a toad, signalling with a war-fan to his frog-army to engage with the enemy.

During the Edo period, many comic works appeared, but edicts and restrictions by the government reduced their number. Nonetheless, the news of the events that led to the fall of the military regime was conveyed to the public by means of caricatures and humorous paintings. Today, the manga are known principally as the Japanese comic books.nd are unsigned and undated.

Works by some of the ukiyo-e artists (Ukiyo-e: Pictures from the Floating World) are also painted with much humour. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the woodblock prints of Toshusai Sharaku (active 1794-1795) and Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825) were caricatures of Kabuki actors with grotesque facial expressions. In 1814, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1848) published 13 volumes of sketches known as the "Hokusai Manga". Two more volumes were published after his death. Hokusai was the first to use the term ‘manga' for his series of prints of people, animals, and everything under the sun. The artist had not intended to create a series of humorous works, but they reflect the comic element in scenes of daily life. Hokusai's manga are characterized by swift, firm, free lines. On the back of his comic sketches Hokusai signed himself as "painted by a madman" (Gakyojin), or "Crazy paintings by an old man" (Gakyo Rojin). Thus, "kyoga", meaning ‘crazy paintings', was a term applied to comic paintings. Many artists, like Utagawa Toyokuni, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858) had a special signature for their humorous prints, for instance "Hiroshige giga" or "Hiroshige gihitsu" - i.e. "Hiroshige's caricature".

In Japan there has been a long tradition of humorous representations of political or social subjects that incorporate animals. The woodblock print by Kawanabe Kyosai, for instance, "An Elegant Picture of the Great Frog Battle", depicts a battle that was to take place between the Shogun's army and the warriors of the feudal aristocracy. The print shows the Shogun commander as a frog riding on a toad, signalling with a war-fan to his frog-army to engage with the enemy.

During the Edo period, many comic works appeared, but edicts and restrictions by the government reduced their number. Nonetheless, the news of the events that led to the fall of the military regime was conveyed to the public by means of caricatures and humorous paintings. Today, the manga are known principally as the Japanese comic books.