In the year 1600 a Dutch boat was swept onto the coast at Kyushu, with a British navigator named William Adams (d. 1620) on board. Adams remained in Japan as adviser to the Shogun in regard to trade with the West. He worked to develop commercial contacts between Japan and Holland and Great Britain, and warned the Shogun against the Portuguese, the Spanish, and the missionaries of the Catholic church. In 1614 an edict forbidding Christianity was published in Japan, and the foreign missionaries were commanded to leave the country. In 1624 all Spanish merchants were also expelled, as were the Portuguese in 1636. Although the British traders were not ordered to leave, they decided that trade with Japan was unprofitable because of the restrictions imposed on it, and departed of their own free will. Thus began the period in Japan known as Sakoku (seclusion), which prevailed for more than two hundred years.

The Dutch traders, on the other hand, decided to remain in Japan even though they were commanded, in 1641, to take up residence on Deshima, the artificial island near Nagasaki. This island, covering about half a square kilometre, is linked to the shore by a bridge, and only a few Dutch citizens were permitted to reside there. The Dutch thus gained a monopoly of trade between Japan and the West during the two hundred years of sakoku. Chinese merchants were also permitted to remain in Japan, but in 1866 the only area in which they could live was a stretch of 180 sq. metres along the bay at Deshima.

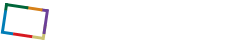

The woodblock prints created at Nagasaki (Nagasaki-e: Nagasaki pictures) between 1750 and 1850 depict the foreigners arriving at the only port where they were allowed entry. The prints show the citizens and the Dutch traders, their clothing and their customs, like sitting around a table, or their exotic belongings such as the cutlery they used for eating. Chinese merchants were also depicted, visiting the temples in the city for their own religious ceremonies. Initially, these prints were sold as cheap souvenirs (Nagasaki miyage) to visitors from other parts of Japan. Most of the local artists who depicted the Dutchmen and the Chinese were not famous in their time, but their prints have much artistic and historical value.

The Nagasaki prints differ both in style and in technique from the Ukiyo-e ("Pictures of the Floating World") prints that showed the daily life of the Japanese in their own land. The Nagasaki prints were printed on paper of poorer quality, and were coloured either by hand or by means of a stencil, and were mainly influenced by European prints and Chinese painting. Only at the end of the Edo era (Edo: 1603-1868) did the artists begin to make coloured prints from separate wooden blocks, like the ukiyo-e.

Japan's seclusion came to an end in 1854, when the American Commodore Matthew Perry (1794-1858) and a convoy of warships dropped anchor in the Bay at Edo (Tokyo). The Japanese called the American steamships "the black ships" because of their colour. Perry demanded that Japan should open its gates, and in March 1854 the shogun's emissaries signed a treaty of peace and friendship with the United States. This treaty led the Japanese to sign a trade agreement with four other countries in 1858, namely Great Britain, Holland, France and Russia, and to open some of the ports to foreigners.

In 1860, the Shogun Government allotted to the foreigners the fishing village of Yokohama, south of Edo, so that they could make their home there. Brick houses in the western style were built, and the town became Japan's international commercial centre. In 1869 there were about 16,000 foreigners exporting tea, cotton, and silk, and importing everything else. In the streets of Yokohama, the Japanese could learn about the clothing, the food, the homes and the customs of the West. Foreigners coming from Shanghai brought their Chinese servants with them. Opening Japan's gates created the social revolution that was the downfall of the feudal government.

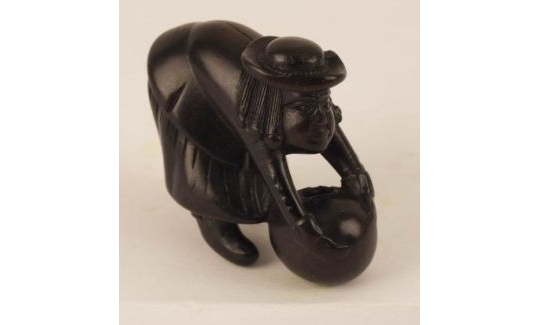

The prints known as Yokohama-e (Yokohama pictures) depict the town and its foreign inhabitants from 1859 until the 1870s. They were sold in little bookshops, usually in series of five (the number of foreign countries whose citizens were living in Japan), or in series of six with the addition of China, even though the latter had no official agreement but was allowed to trade with Japan. In 1858-1862, thirty-one artists created more than 500 designs for prints, that were then printed by some fifty publishers.

The Yokohama prints published in Edo were created by artists of the Utagawa School, among whom were Utagawa Yoshiiku (1833-1904), Utagawa Yoshikazu (worked c. 1850-1870), and Utagawa Yoshitora (worked c. 1850-1880) and others.

Yokohama was not far from Edo, but at that time unrestricted travel was forbidden to Japanese and foreigners alike. Since most of the artists received their impressions of how the foreigners looked and how they lived from the western newspapers and journals that were beginning to arrived in Japan, all sorts of fascinating anomalies are apparent in their prints. For example, a print by Utagawa Yoshikazu depicts "foreign residents enjoying a party". The port of Yokohama can be seen through the window, but the scene is actually a celebration in honour of the first Japanese Ambassador, held at the Willard Hotel in Washington D.C. (today the Willard Intercontinental), in 1860. The little girl dancing in the centre actually danced at a children's party that took place in May that year. The artist was certainly not present at the event, and even added a wall clock that he had seen in prints of a Dutch interior on Deshima. One of the preferred formats for the Yokohama prints was the triptych.

It is evident from the prints that the Japanese were fascinated by the clothing, the strange habits and the occupations of the foreigners. This gave rise to imaginary representations of other countries such as the blue print by Utagawa Yoshikazu of Washington. The attempts of the Japanese artists to depict the foreign merchants and residents also led to humorous representations. In a print by Hiroshige II (1826-1869), an American woman is wearing a feather head-dress like those worn by American Indians. Such prints were even popular with the foreigners themselves.

The exhibition also presents coloured prints from the Meiji era (1868-1912) that demonstrate the influence of western culture on Japan, evident in the western style clothing and architecture.