This year, Japan celebrates four hundred years since the beginning of the Edo era. In 1603, after long years of bloody civil wars, the Tokugawa dynasty came to power in Japan, and established a military government that lasted until 1868. The seat of government was in Edo (today Tokyo) which developed into one of the world's largest cities at the beginning of the 17th century, with some one million inhabitants. During the Edo period, Japan was a peaceful, economically prosperous country, almost completely cut off from the western world for more than 200 years, until the arrival of the American fleet in 1854.

In order to maintain political and social order, a hierarchy was established, demarcating the status of the lords (samurai) and the lower orders (peasants, craftsmen and merchants). Titles were inherited, and moving up the social ladder was forbidden. With peace and stability established, some of the samurai became redundant, and the traditional aristocracy lost its economic ascendancy. The merchants, craftsmen and workers who had settled in the towns became "townsmen" (chonin). The conservative feudal government imposed several edicts on the merchants. They were forbidden, for example, to wear silk clothing or to build costly mansions. However, these impositions, intended to preserve the established status quo, did not affect the merchants' prosperity. The sense of security created by peace and stability encouraged the development of trading and reinforced their standing. Education, which had previously been the privilege of the upper classes, was now accessible to the lower orders.

The wealth of the tradesmen led to the development of a specific city culture and a new theme in art - Ukiyo ("The FloatingWorld"). Originally "ukiyo" was a Buddhist concept, denoting the world as a transitory place full of suffering. But at the beginning of Edo, the expression acquired a new meaning - the ephemeral world of wealth and pleasure, passing like a gourd floating on the waves of the sea. The Floating World was an illusion, the embodiment of the life without care of the new bourgeoisie, fashionable and sophisticated. For the first time in Japan's history, the lower classes were dictating the cultural mores.

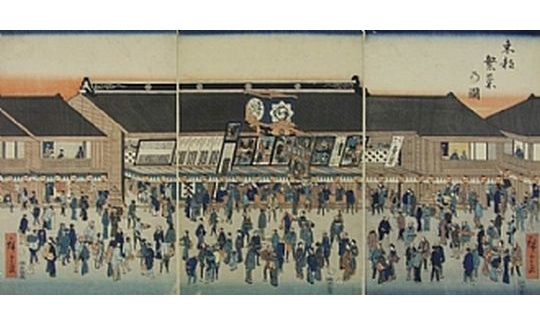

The art depicting this new society was called "Ukiyo-e" - Pictures from the Floating World. It presented the leisure activities that the city-dwellers could now afford. Initially, the ukiyo-e were influenced by the classic style of the Kano School. Scrolls and gilded folding screens were decorated, and subjects included the pleasure quarters and their visitors, Kabuki actors and theatres, courtesans and geishas, tea houses, sumo wrestlers, views of Japan and of the big cities, including Edo itself. By the end of the era, this was the culture that prevailed throughout Japan, though the artists' works, which were usually not political, were subject to strict censorship by the officials of the military government.

The technique of woodblock printing was developed in the Edo period, allowing works of art to be printed in multiple copies, each block a source of virtually unlimited reproductions. First the illustrated book (ehon) appeared, with black and white woodblock prints, sometimes hand-painted. This was followed by coloured prints, each colour printed from a separate block. This was art for the middle classes, and it was natural for the ukiyo-e artists to depict the pleasure quarters of the big cities where the citizens could show off their prosperity. Unlike the traditional Japanese art reserved for the aristocracy, the woodblock prints were accessible to the less affluent.

In 1635, the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, instigated a law according to which every feudal baron (daimyo) was obliged to spend six months of each year in Edo as "a duty in the lord's service" (sankin kotai). This law was also partly responsible for the rise of the pleasure quarters, particularly in Edo since the daimyo came to Edo accompanied by hundreds of soldiers. An illustration of this can be seen in the print "The Daimyo's Procession" by Keisai Eisen.

The artists depictions of life in the pleasure quarters incorporated the men enjoying themselves - rich merchants, feudal barons, samurai, and sometimes even monks who were forbidden to be there since it was detrimental to their reputation, because anyone involved in the business of pleasure, like courtesans or actors, was a social outcast. They were "non-people" (hinin). Nonetheless, the ukiyo-e genre depicting beautiful women (bijin-ga), the refined and elegant courtesans, shows them as ideals of womanhood. See, for instance, the "Standing Courtesan" by Ando Kaigetsudo.

The pleasure quarter is also linked to the development of the Kabuki theatre in the 17th century. Ironically, the Kabuki, identified in our day as the theatre in which all the actors are male, was originally a production by a woman, in which women also played the male roles. These pleasure girls used the stage to display their attractions, and sold their bodies after the performance. In 1629, when clients in the audience began fighting for the favours of the actresses and disturbing the public order, the shogun forbade women to appear on stage. They were replaced by handsome young men, so that acting again became a vehicle for erotic display to arouse sexual attraction, and this was again forbidden by the shogun in 1652, as was erotic dancing on stage. Only adult men were now permitted to perform at the Kabuki theatre, and they too appeared in the female roles (onna-gata). These female impersonators were experts at portraying feminine gestures and speech. Their acting was so convincing that they ultimately became role-models for women. Tastes in Kabuki theatre varied: in Osaka and Kyoto the refined style (wagoto) was preferred, soft and feminine, with heart-rending dramas of love and suicide. The people of Edo preferred the coarser dramas of adventure, courage, and manliness (aragoto). Woodblock prints of the Kabuki (yakusha-e) were of theatrical scenes and famous Kabuki actors. Artists in Osaka and Kyoto preferred the refined tradition characteristic of the court aristocracy, whereas the Edo artists developed a completely new genre with no reference to tradition.

In the 18th century, the print artists who depicted the Kabuki theatre also began to show interest in sumo wrestling, which had come to Edo from Kyoto via Osaka. The rules of sumo are simple: to tumble one's opponent or to push him out of the ring. Each bout lasted only a few minutes. On the other hand, the ceremonial entry into the ring before a match took much longer. The wrestlers enter the ring wearing an embroidered silk apron. They purify themselves with a drink of water. They stamp their feet, clap their hands, and then extend their arms, palms upward. They strew salt to purify the ring, and prepare to fight. Prints depicting sumo wrestlers at all stages of a match were produced mainly by artists of the Katsugawa and Utagawa Schools, who had gained renown largely because of their prints of Kabuki actors.

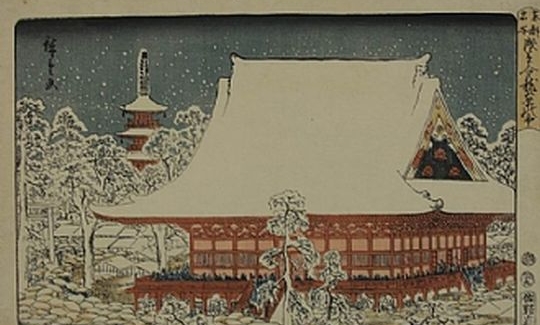

Landscape was a focal motif of the Japanese artists up to the 17th century, and many of them were influenced by Chinese landscape paintings. The ukiyo-e artists, on the other hand, preferred the landscapes of Japan and, together with famous views, they depicted ordinary people going about their business or travelling. This is evident in the works of Katsushika Hokusai and the artists of the Utagawa School, especially of Ando Hiroshige. Studying the ukiyo-e prints, we can see that the artists' interest was the human element. They depicted the simple people, everyday life, and their works embody the strivings of the outcasts and the lower classes of a feudal society to live and thrive. However, apart from a few examples, one can hardly say that these works are realistic. The artists presented an idealized view rather than actual reality.

Throughout their history, the Japanese have carefully preserved their heritage of tradition. The new spirit that began in Edo could not replace the traditional Japanese arts - Japanese painting (yamato-e) that began in the mid-9th century, or the Noh Theatre begun in the 14th century. Nonetheless, the Edo era was also the last golden age of some traditional Japanese crafts, such as the lacquer ware that originated in antiquity, or the netsuke (small carvings intended to prevent accessories from becoming detached from a sash) that first appeared in the 15th century. The middle classes of the period were thirsty for elegant and impressive works of art. Their desire for pomp and circumstance is partly responsible for special techniques in creating wares for daily use, such as gilded lacquer containers for seals (inro), writing boxes (suzuri-bako), or the animal, human and vegetable netsuke carvings, that reached their apex during the Edo era.

When the American commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Japan in 1854, he brought a western world to a country that was still feudal, in which virtually everything was hand-made. In a short time, the Japanese had assimilated the technologies and life style of the West, and a fascinating dialogue began, and continues, between the modern western world and the Japanese tradition.