Japanese tradition is rich in legends and folktales that are also represented in the plastic arts, forming a body of work indivisible from the culture of Japan. As in the rest of the world, the fables (densetsu) and folktales (mukashi-banashi: ancient stories) embody the moral values and way of life of the country. The term "mukashi-banashi" emphasizes the difference between folktales and the fables about wonderful events that people truly believe to have occurred.

Many Japanese tales and fables derive from those of other lands, in particular from India (Buddhist legends), China (Taoism), and sometimes from Tibet, Burma, and Korea, which have gradually acquired local Japanese characteristics. In addition, there are two types of story indigenous to Japan - those rooted in the Shinto myths, the oldest religion in Japan, already practiced some 1200 years before Buddhism was adopted in the 6th century; and those based on heroic deeds of medieval times.

The Shinto faith and the ancient myths of Japan nourished its folklore and the popular beliefs with stories and legends about gods, demons, and ghosts. The Shinto belief that everything that exists has a soul is another source of the demonic creatures that have made their way into these tales. Buddhism has also contributed generously to Japanese folklore, with tales about Buddha's wanderings and the lives of other religious figures. The transmigration of souls, for instance, is considered to account for the existence of various gods and demons.

Although Taoism has never become an official religion in Japan, the Taoist beliefs, originating in China, do appear in the literature and in art. Stories of the Chinese immortals reached Japan in medieval times, together with Chinese tales of magicians and ascetics, miracles and other wonders. The first evidence of their appearance in Japan is the "Anthology of Stories from the Past" (Konjaku Monogatarishu) from the 12th century. Here one can find Japanese folk tales together with Chinese and Indian legends.

Another type of original Japanese fable or folktale was inspired by the sagas of heroic deeds and daring by dauntless warriors who participated in the civil wars that fill the pages of Japanese history, and the adventures of Buddhist monks or successful members of the emperor's court. Most of these tales are set in the 9th-11th centuries, the classic age of Japanese culture. Over time, these deeds have become stories in which fact and fiction are indistinguishable. Most of them were passed on orally from one generation to the next until writing appeared in Japan in the 6th century. They were later written down by literate members of the elite.

It seems that the earliest written works, from the 8th century are the Urashima Taro that appears in the early lists of the Tango Fudoki (713 C.E.), and the Takatori Monogatari - the "Tale of the Bamboo Cutter". Such stories frequently describe the figures and strange creatures that sometrimes appear in supernatural form. Kaguyahime, for example, is the beautiful daughter of the moon, discovered by the bamboo cutter inside a bamboo cane. Momotaro is the boy born out of a peach kernel. Others, like Hanasaka-jiji, the old man who made the camellias bloom, are intended to explain natural effects in an enjoyable fashion, and with moral values. The fables also reflect the wish to comprehend the laws of the universe and the forces of nature.

In every country there are stories about talking animals, and Japan is no exception. Animals play an important role in mythology and fable, both in their own right, and in connection with immortal beings or deities. They are either grateful or malicious towards mankind. They can talk to each other and to people. In real life there have even been people who assert that animals have human qualities and abilities, and in the myths these traits are greatly exaggerated.

The dragon is the most ancient mythological beast, one that usually requires a human sacrifice. Susano-o no Mikoto found a magic sword in the dragon's tail. The wife of Yamamoto threw herself into the sea to pacify the dragon.

The fox is the most ancient of creatures, and stories about him concern immortality. The fox is the envoy of the rice god Inari, and sometimes the god himself is represented as a fox. Like other animals, the fox can change into a human being, though he does not do this as often as the snake or the dragon. The Nihon Ryoiki - the "Wonderful Tales from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition" of the 9th century includes a tale of a fox who became a woman.

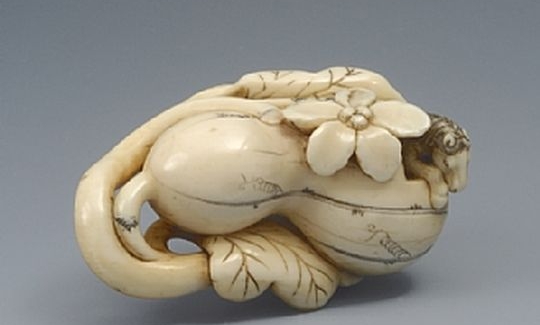

The dog, the cat, the hare and the tanuki - a kind of raccoon - also appear frequently. The tanuki is a strange creature, cunning, able to change shape, that knows how to repay a kindness, but is also, sometimes, a simpleton who is easily deceived. A tanuki depicted as a Buddhist monk symbolizes wisdom and gratitude.

The two oldest compilations from the 8th century are the Kojiki - Collected Ancient Tales (712 C.E.), and the Nihon-shoki - the Japanese Chronicle (720 C.E.). The creation of the heavens and the earth is described in both of them, as are the arrival of the gods and events that occurred in Japan long, long ago. The story of the bamboo cutter is a good example of Japanese romantic literature of the period, and essentially describes the customs of the court in Heian (today Kyoto). In the Kojiki, stories of gods who became human are also to be found, as well as humans who become birds, and animals, plants and views of all kinds.

The earliest woodblock prints created in Japan in the 17th century were first published in illustrated books (Ehon), some of which were folk tales and fables. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Japanese artist Tachibana no Marukuni made more than 100 illustrations for these stories. One of the most famous artists of all time, Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) created the Hokusai manga, a rich collection of preparatory sketches for such works that have since inspired the illustrations of countless artists.

Legends and folk tales have also inspired traditional Japanese dance and theatre - the Noh Theatre of the 14th century and the Kabuki that began in the early 17th century, both of which are flourishing today. The performances and plays also provide unlimited sources of inspiration for Japanese artists and craftsmen - painters, designers, sculptors, potters, and others.

In this exhibition from the Museum's collection, you will find netsuke, lacquer wares, painting, prints, drawings, sword fittings and more, all illustrating the marvellous imaginary deeds of legend and fable.