In China, ideograms developed from paintings, and the script became integral to the work of art, especially to painting. In a Chinese dictionary of the 1st century, the ideogram for "writing" and "painting" is the same, and represents a hand holding a brush, drawing a frame round a space. Many strokes characteristic of the simple script are also used in painting. The Japanese adopted the Chinese symbols in the 6th century. Even today, the meaning of the Japanese "kaku" is both "to paint" and "to write", though they are each written with a different symbol. Thus calligraphy and painting are closely associated, both in China and in Japan. In the early ink drawings it was customary to include "gasen" (writing). Gasen is original prose or verse, or a quotation from classic literature or poetry. In some instances, the text is added by a friend or admirer of the artist, in others by the artist himself. Under the text the signature and seal of the poet are added. It was customary for the Zen masters to add words of encouragement or praise for their pupils to a painting, which were then given as gifts in appreciation of the students' achievements.

In the early 15th century, the "shigajiku" (poem-picture scroll) was a favourite mode of expression in Japan. These were usually landscapes accompanied by poems. Shigajiku evolved in the five Zen mountain temples (gozan) of Kyoto. A very famous shigajiku is by the Zen monk Josetsu (active 1386?-1428?) "Catching catfish in a gourd" in the Taizoin Temple. In the upper section of the painting, poems by thirty Zen monks are inscribed. Many works are attributed to the artist Shubun, active 1414-1463 in the Muromachi era (1333-1573), and these too include writings by Zen monks. Similar to the shigajiku are the "shosaijiku" or "shosai-zu" - painted scrolls depicting monks studying in isolated retreats or monasteries, with a poem in the upper section. Sobetsujiku scrolls also include pictures and poems, and depict the sadness of a family member departing from home to lead a monastic life. When the Japanese artist Sesshu

(1420-1506) went to China to paint scenery there from personal observation, the link between ink painting and Zen monasteries with literature ceased, and paintings without texts began to appear.

Poetry has been part of Japanese culture since the dawn of civilization. Even the historical epic "Kojiki" ("Sketches of Ancient Things") edited in the 8th century includes poems. The first Japanese poetry anthology, the "Manyoshu" ("Collection of a thousand leaves"), also of the 8th century, contains more than 4000 poems, each of 5-7 stanzas, some short, some longer. After the Manyoshu, the long poem was replaced by the "tanka" (short poem), also known as "waka" (Japanese poem). The tanka has 31 lines (7-7-5-7-5), does not usually rhyme, and comprises two themes - descriptions of scenery and of the poet's emotions. In the Heian era (794-1185), poetry contests were held at the emperor's court, and anthologies like the "Kokinshu" (Anthology of old and new Japanese poetry, 905) were compiled at his command. In the same period, in addition to the traditional tanka, we also find the "kanshi" - the Chinese form - which has a standard number of syllables in each line (4,5,7,8 or more) and no syntactical connection between the lines, which generally rhyme. The "haiku", composed of 17 syllables (5-7-5) developed in the 16th century, and is really an abbreviated form of the tanka, borrowing the mental outlook of the poet - natural scenes intended to convey emotions, thought, and moods. Two other poetic modes that also developed were the "kyoka" (crazy poem), and the "senryu", so called after the poet Karai Senryu (1718-1790). The kyoka is a satirical tanka, while the senryu is a humorous haiku that is sometimes shorter than the standard. The comic tanka became very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries in Kyoto, and later in Edo. The kyoka depends largely on word play, double entendres, and imitations of classic poetry. However, it lacks the more countrified simplicity typical of the senryu. The first kyoka anthologies were published in Kyoto circa 1760. Chinese poetry, and humorous versions of it, the "kyoshi" (crazy Chinese poems) were also frequently integrated as gasen.

During the Edo era (1603-1868), the long tradition of poem-paintings also began to appear as "ukiyo-e" (pictures from the floating world), the woodblock print genre. Most of the early prints were black-and-white, and their subjects were usually kabuki actors or courtesans. Often they appeared without the signature of the poet, and these can be attributed to the actors or courtesans depicted. In other instances, the connection between painting and poem derived from the need to mark some specific event - the first performance by a kabuki actor in Edo; changing the actor's name; if he appeared in a particularly long drama. Most of these prints were created by artists of the Torii school.

Poetry was integral to life in Edo (today Tokyo), and all strata of society, from samurai to courtesan, wrote poems. This feeling for poetry gave rise to many poets' clubs and groups. In 1769, a group of poets came together to write poems, among whom were Karagoromo Kisshu (1743-1802) and Yomo no Akara (1749-1823) who was Ota Nampo. Thus the kyoka club was formed. The poets frequently invited an artist to illustrate the subject selected for composition, and this in turn gave rise to the "surimono" ("something printed"). Most artists of the time who created surimono prints - greeting cards or invitations to performances or concerts - wrote poetry and belonged to such clubs. Kisshu wrote in his journal that each poet would bring a decorated cloth or a fan with a poem on it to the meetings. In the 1760s, the kyoka was very popular in Edo. Poets, artists and tradesmen alike wrote kyoka that influenced the popular art of the time.

Although ukiyo-e is considered a popular art form, it is still closely linked to the classic Japanese culture. This is evident in the integration of classic tanka poems in the paintings or prints, many of which illustrate the content of the text or the circumstances of its composition. Classic Japanese literature is full of poetry. Many woodblock prints from the "floating world" comprise these original poems, episodes from the 10th century "Tale of Ise", and poems by Ariwara no Narihira (825-880).

An innovation of the Edo period was illustrating poetry collections. The best known of these is Katsushika Hokusai's "One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets as explained by a Wet-Nurse". A wet-nurse was an uneducated woman, so we can assume that Hokusai dealt with the subject in a humorous fashion.

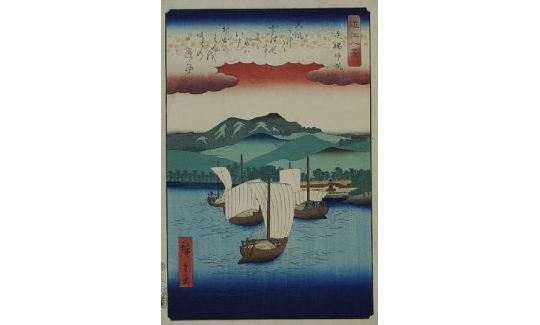

Another famous series that includes poems is the "Omi hakkei" (Eight Views of Omi) by Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858). Possibly the inspiration for these prints was a series of Chinese paintings of the 11th century, depicting "Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers" which include poems written by a Zen monk. A tradition also arose in Japan of "meisho-e" ("pictures of famous places") in the Heian era. Omi is the area near Lake Biwa. Some think that Konoe Masaie (1444-1505) and his son Hisamichi (1472-1544) chose the sites for the series and composed the poems, but many of today's experts believe that they were written by the calligrapher Konoe Nobutada (1565-1614). At Enman'in, the temple at Miidera, there are two folding screens decorated with representations of Omi and the poems by Nobutada, which are thought to be the earliest works on the subject. At the beginning of the 17th century, the same subject became part of the repertoire of the Kano school that was connected with the military regime, and of the Tosa school at the court of the emperor. One of the early ukiyo-e artists was Nishimura Shigenaga (1697?-1756), who created four different series of prints on this theme. Perhaps Ishiyama was the place most frequently depicted in the series because, according to tradition, Murasaki Shikibu wrote her "Genji Monogatari" (Tale of Genji) at the temple, completing it in 1008. A print by Kuniyoshi shows the temple's main hall looking out across Lake Biwa, with a full moon shining between the clouds:

Ishiyama!

The moon shining

over Niho Bay

is the very same

as at Suma and Akashi.

The poet imagines Murasaki in the temple at Ishiyama, watching the moonlight on Lake Biwa, the very same moon that shines over the sea at Akashi, near the inland sea; and on Suma, near Osaka, where Prince Genji, the hero of her novel, is located.

Japanese artists did not confine themselves to "eight famous views of Omi". They illustrated other series of views and poems about the districts of Japan. Kanazawa was one of these, and the print "Autumn Moon at Seto" comes from his series.

The six Tamagawa rivers (Jewel Rivers) were also popular subjects for woodblock prints. Each print deals with a specific scene or an event that occurred there. In the "Tetsukuri no Tamagawa" print, for example, the poem emphasizes the taste of the water flowing towards the temple on Mount Koya:

Despite the warning,

Despite the bitter taste,

The traveller to Okuno in Takano

Gulps the water from Tamagawa River.

Apparently the rivers are valued for their potability, though a notice beside them warns against drinking because the water is polluted by poisonous insects. The poem suggests tasting it first.

Laments for death also appear in the prints and paintings. Toyokuni III's portrait of Ando Hiroshige incorporates a biographical text of the latter, written by the poet and author Tenmei Rojin. On the left is the following poem:

I leave

my paintbrush in the East,

travelling skies

I long to see

the famous Western Land.

To the east lies Edo, Hiroshige's homeland. According to Buddhist belief, the Western Land is Paradise.

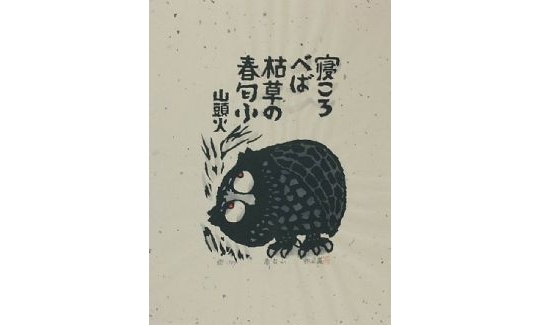

In the 17th century the haiga appeared, a combination of haiku and spontaneous ink painting. Some of the gasen (texts) on these works were considered of more value than the paintings themselves, which led to detaching them and displaying them on a separate scroll.

The Hebrew translations of the poems in the exhibition are all in the free style demanded by the Japanese poetic form. Each word has been carefully and sensitively chosen. I have also tried to render and place the words in their original poetic order.