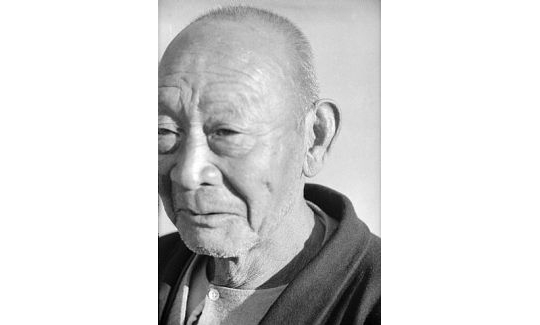

Ze'ev (Wilhelm) Aleksandrowicz was born in Cracow in 1905, the only son of well-established family of paper merchants. In his childhood he received a sound Jewish and Zionist education, and his first camera was a gift from his aunt. His parents had hoped that he would enter the family business when he grew up, but he was determined to live his life according to his own intentions. So, after completing his schooling, he set out on his travels through Poland and other countries, with his camera on his shoulder.

Aleksandrowicz never studied photography formally, and referred to himself as an "amateur photographer". He died in Tel Aviv in 1992. Eleven years after his death, thousands of rolls of film were discovered quite by chance at his home, stored in little tins in an old suitcase. Most of the photographs were taken in the countries he visited, and in Israel. They were taken between 1931-1936, with two Leica cameras, on 35 mm. black-and-white film, and most of them were not printed during his lifetime. In 1934, the climax of his travels worldwide, he arrived in Japan, and during the few weeks that he was there he took hundreds of photographs.

Aleksandrowicz had already begun to document his trip to Japan during the voyage from San Francisco to Yokohama. There were many American-born Japanese on board. On deck he photographed a group of them practicing martial arts (kendo) with special practice swords made of split bamboo (shinai). He became friendly with them, and asked in all innocence whether he would be able to meet the emperor. They looked at this foreigner who knew nothing at all about Japan, and informed him that (at that time) this was strictly forbidden - "But I visited the palace when he wasn't at home", wrote Aleksandrowicz in his journal.

He photographed the cities and the many other sites he visited - Tokyo, Kyoto, Nara, Nikko, and others. But he did not only register the places in his camera's eye. His photographs convey his love for humanity, for the people whom he depicts with such a rare combination of sensitivity and clearsightedness. After the earthquake that destroyed Tokyo in 1923, the city was rebuilt as a modern metropolis with western architecture. Aleksandrowicz's photographs of Tokyo convey this progress on one hand, and the retaining of tradition on the other. An example of this is a woman wearing a traditional Japanese garment, holding a baby in her arms, and looking in the window of a shop displaying western-style clothing. Other photographs are of Japanese men in traditional garb with western hats on their heads, and of a woman pulling a cart past an electric tram.

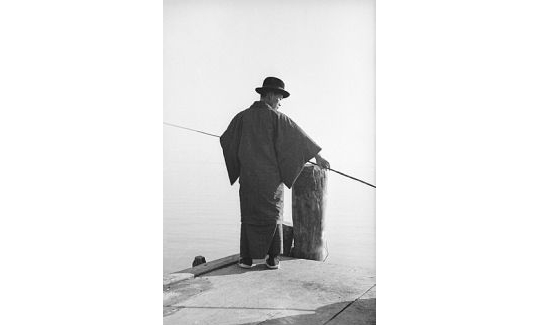

But what really makes Ze'ev Aleksandrowicz's photographs so fascinating is their composition, which often brings Zen painting to mind. There is one, for instance, of a fisherman with his rod. The rod, like the branch with a bird perched on it in a famous Zen painting, crosses the photograph diagonally from left to right. The figure and the rod, like the bird on the branch, are not centred in the picture, but in spite of this asymmetry, the composition is perfectly balanced. Another photograph that illustrates Aleksandrowicz's ability to depict a "universe in a grain of sand" juxtaposes "empty" and "full" spaces. A little boy bends down. Again, he is not at the centre of the image. His attitude and the shadow he casts create the balance. In yet another picture, a woman climbs an endless flight of steps with a child on her back. The steps form a diagonal that shifts from side to side, and the figure is enclosed in an "empty" space.

Ze'ev Aleksandrowicz found his truth even in small, often insignificant, matters. His lens registered people seated on a public bench, each of them looking in a different direction. He caught the typically Japanese mannerism of carefully not staring at or infringing on the space of others.

During the 1930s, Japanese militarism reached its apogee with the conquest of Manchuria, but this is barely evident in Aleksandrowicz's photographs. Conversely, poverty, especially among the peasants and tenant farmers is very conspicuous. Economic decline began in Japan in 1930 as a result of the depression worldwide. Income from raw silk exported to America decreased, as a result of which two million Japanese peasant families (approximately one-third of the rural population) were impoverished. Prices of rice and other produce fell, and earnings from agriculture were reduced to one-third of what they had been in the preceding four years. The tenant farmers were unable to pay their rents and fell heavily into debt. In 1931 there was a drought in north-eastern Japan, and millions of peasants endured famine. The depression also affected industries, many of which closed down. The number of unemployed rose to about three million - at a time of demographic increase.

The invasion of Manchuria did help Japan to cope with its economic problems, and the heavy industries profited from re-equipping the army, though it had almost no effect on the peasants represented in Aleksandrowicz's photographs.

"For me, Japan was something out of the ordinary - as if I were on Mars", said Aleksandrowicz, and registered in black and white a world full of colour.