It was ten years ago that I first encountered the works of the artist Noriko Yanagisawa. That was when we were planning her first exhibition at the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art in Haifa, Israel. The works consisted of etchings in which the same images appeared repeatedly, among them a headless man, a scrawny dog, a bird's (or angel's) wing, broken branches, and fossils. Even at that time I sensed that these motifs were "ideograms" representing concepts that Yanagisawa herself had created over the years. Those concepts invite the spectator to "read" the works as if looking into a book.

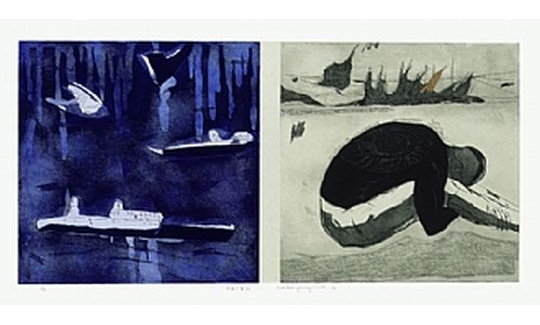

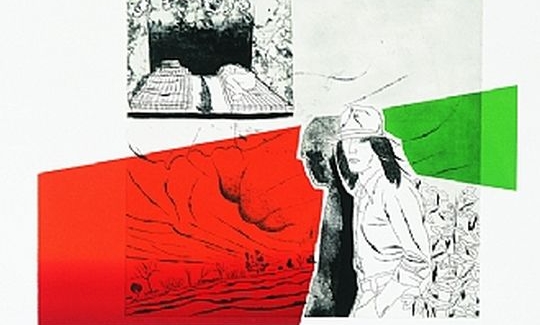

The tales related in the paintings and prints (even if they are not actual narratives) are not set in any specific environment. They are universal. The motifs, which are closely associated with mankind's acts on the face of the earth, are swathed in heartwarming primary colours - reds, yellows and blues, compounded with vibrant, almost celestial purple, orange and green. The artist works with coloured inks, and sometimes affixes patches of Japanese and/or drafting paper, or delicate areas of feathery down to her work.

It seems that the universal headless (and perhaps also heedless) man, frequently depicted in the darkest of hues, is he who destroys the rain forests (the dry, broken branches), and changes the weather patterns, creating drought and starvation (the scrawny dog). Are we looking at ourselves? Are we really responsible for cutting off the only branch that remains, the one on which we ourselves are sitting? This does seem to be the case, and a hint of it is present in a painting in which the man has only four fingers. Is this the result of war, or of genetic mutation deriving from a nuclear holocaust? The fossils that are so often there on the man's back are like memorials or tombstones - all that remains of the past. They are "registered" in the history of nature, as deeds of the present are registered in those ideograms.

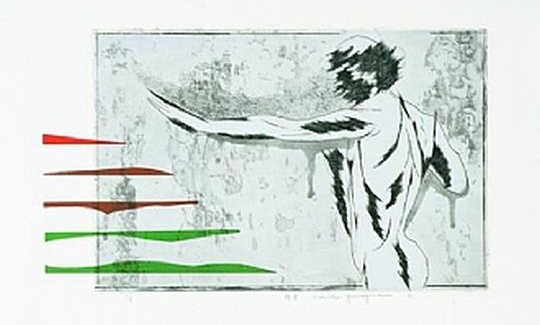

At the same time, Noriko Yanagisawa does not offer visions or prophecies. Her paintings are like bubbles, reflecting us as in a mirror. To understand what we are seeing we do not need to be sophisticated, but simply to be clear-sighted. After all, the reflection is of a reality that we know all too well - Chernobyl, the irreversible damage to the ozone layer, and all the rest. Just as a mirror passes no judgment for good or evil, neither does Yanagisawa tip the scales. She gives each motif in her works equal weight, equal merit. There they are, juxtaposed, side by side. She does not accentuate this motif or that by chiaroscuro or any other form of emphasis. Impartially, she shows us nature on one hand - and on the other, our preferred object of study, ourselves amid the beauties of nature. The discrete wing that is so often present, the downy feathers that she sometimes affixes to her paintings are symbols of flight into another (a better?) future. Even so, time and events seem to be immobilized, and the transience of eternity gives way to the eternity of the moment.

The clearest Japanese aesthetic values are rooted in Yanagisawa's works, exemplified by her predilection for what is lacking - i.e. absence - over what is complete - i.e. presence. The classic western concept of perfect beauty is distilled in the human form, but Yanagisawa depicts it devoid of some of its elements. Neither is the bird/angel or the branch "whole". This ideal of beauty deriving from what is lacking is an aesthetic value described in "Essays in Idleness" (Tsurezuregusa) by Kenko Yoshido (1330; pt.137): Are we supposed to look at the cherry blossom only when it is in full bloom; or at the moon only on a cloudless night?... Branches that are about to flower, and gardens strewn with withered blooms are more worthy of our appreciation... The moon that appears just before dawn, after we have waited so long to see it, affects us more deeply than a full moon that lights up the whole sky...