The fan is an important accessory in the Japanese culture. Their purpose is not merely for fanning, they are emblems of status and a practical embellishment, used by men and women alike, and they play an important role in the life of the Japanese.

There are two main types of fan in Japan. The first fans were brought from China via Korea during the 6th century CE. These were hard, flat ovals, known in Japan as uchiwa. The familiar folding fan, the ogi or sensu, was apparently invented during the reign of the Emperor Tenji (661-672). Both types are still in use, though the folding fan is more popular.

In the past, craftsmen created fans at home, but today only a few still preserve this tradition. The frame of the folding fan is usually made of bamboo, while ivory is used for the more elegant ones. The number of ribs varies between 3 and 80, and they are covered with paper or silk ornamented with painting or calligraphy.

In the Heian era (794-1185) the aristocracy used fans as part of their official garb, and the number of ribs in the fan was adjusted to the status of its owner. The samurai also used fans, known as jinsen, made of pheasant or peacock feathers. However, their battle fans (gunsen, tessen) had iron ribs, and were used as weapons if necessary. It was thus possible to ascertain a person's rank or occupation according to his fan.

Today, Japanese men and women are still using fans. They are exchanged by engaged couples, and it is also customary to present them as gifts. Sometimes they are purely decorative, and sometimes they are used in such events as the tea ceremony, traditional Japanese dances, and the theatre. Those used in the theatre are decorated with figures related to the drama being performed. Those intended for daily use have no specific motifs. The most popular embellishments include carefully inscribed poetry, calligraphy of Chinese symbols, views, animals, and others.

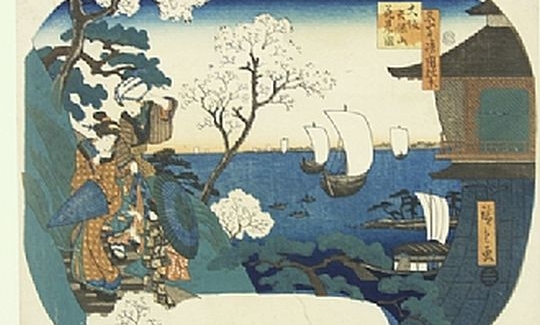

Fans decorated by famous artists are highly valued in Japan. Because of the special composition necessitated by the curve of the paper, Japanese artists began to cut paper into the fan shape (ogi-e: fan pictures) even when it was not intended for this purpose.

The tradition of designing fan-shaped prints arose during the second half of the 18th century. Prints for embellishing fans for daily use are usually of the uchiwa type. The wooden board on which the illustration was carved had the upper and lower edges rounded off, so that the print could be easily fitted to the bamboo ribs which are attached to the handle of the fan.

During the 18th century, there were publishing houses such as Dansendo which specialized in producing fan prints. "Dansen" is pronounced in imitation of the Chinese rendering of the Kanji signs, which are also used to represent the word "uchiwa". Such fans were sold by peddlers in the streets, or could be purchased directly from the publishers.

Since the fans were in constant use, the prints were often damaged or completely ruined. Only a few fan prints have survived, which is why they are such rarities. Many of them are from the pattern-books of the fan vendors. For this reason their colours are still so vivid and, in some of them, the lower left corner is stained from constant handling and turning the pages.

Many artists, especially from the 19th century, including Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858) who designed some five hundred fan prints, were intrigued by this format. These artists used the special shape to create prints with unusual compositions which could not have been achieved on standard rectangular sheets of paper.

Fans were constantly in use and many of the paintings on them were spoiled or completely destroyed. Only a few have survived, from which derives their uniqueness.