The woodblock colour prints known as Ukiyo-e (Pictures from the Floating World) were widespread in Japan from the middle of the 17th century to the middle of the 19th century. After about 50 years of bloody civil wars, the Tokugawa government (1603-1868) came to power, bringing two hundred and fifty years of peace and security. This was the time in which the middle dasses came into their own, and prosperity and economic growth encouraged the development of leisure activities. The artists of the print who depicted the pleasure quarters, the Kabuki Theatre and the courtesans, began to show interest, in the eighteenth century, in the sumo wrestling matches which had arrived in Edo (Tokyo) from Kyoto via Osaka. Sumo prints were created by two principal schools of painting in this era. namely the Katsukawa and the Utagawa, which were already known for their prints of the Kabuki. Many of the albums of woodblock prints are concerned with Sumo as a sport. Documents pertaining to wrestling matches of the period help us to establish the date of these prints very accurately. Ironically, these works convey more biographical information about the world of entertainment' than about the artists themselves, artists being in the lowest ranks of the Japanese social hierarchy.

The laws of sumo wrestling are very simple, and the bouts only last for a few minutes, but the ring-entering ceremony, the Dohyo-irl, takes longer. The wrestlers enter the ring wearing splendid silk aprons embroidered with silver and gold thread. They purify themselves by drinking water, stamp their feet, dap their hands, and turn their palms upward, arms outstretched, then sprinkle salt to purify the ring, and prepare to do combat. Print artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries depicted such important items as the garb of the referee, the sword and fan from the world of the samurai, and the use of water and salt derived from the traditional Shinto rituals.

In the Temmei era (1781-1789), the popularity of professional sumo Increased, and it was the latest subject of the entertainment world to become a special category in the art of the woodblock print In 1782 the artists of the Katsukawa School. Shunsho (1726-1792) and his pupils Shunko (1743-1812} and Shunei (1762-1819), who realized the artistic potential of sumo, transferred their attention from the Kabuki Theatre and began making sumo prints, which were acquired by sumo enthusiasts as mementos. The Katsukawa artists created a separate genre of sumo prints. Obviously, the earliest prints show the sumo wrestlers in static poses rather than realistically. The wrestlers are frozen in their places as in the Mie, the climax of the Kabuki play, when everything comes to a momentary standstill. Initially, the artists were unable to deal with artistic depiction of the fat bodies and their movements.

Shunsho, who could portray the Kabuki actors so realistically, soon began to create even more interesting portraits of the sumo wrestlers because they, unlike the actors, wore no makeup. Shunko made many portraits of wrestlers. For him. and for his teacher Shunsho. it was easy, since they used the same figures over and over again in different prints, to hasten the process. Afterwards, other artists adopted the same method, or copied parts of earlier prints. Ando Hiroshige's (1797-1858) prints of scenery were taken from guidebooks, and the Kabuki representations of the Utagawa artists were taken from a permanent collection of drawings. In this way they were able to cope with the increasing demand for pictures of famous sumo wrestlers and Kabuki actors.

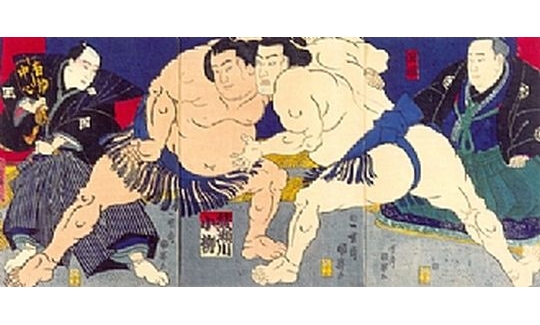

The prints had to be approved by the largest possible section of the pubBc. Nobody wanted an illustration of their favourite being defeated, so that the prints had to be impartial. The faces of both wrestlers had to be shown equally clearly. At first. Katsukawa Shunsho and his pupils paid insufficient attention to this, and portrayed wrestlers looking like masks, or with the lace of one of them concealed. Their lack of knowledge about sumo Is also evident because they drew wrestlers wearing the apron used only in the ring-entering ceremony.

Sumo apparently originated in prehistoric Japan. They say that the gods settled their disputes by means of wrestling contests. Another theory is that the sport, like Buddhism, reached Japan from India, by way of China. The first contest, identified as the ancestor of modem sumo, took place before the emperor in the year 23 BCE, between Sukune and Kuehaya, who fought in their underwear. The contestants fought to the death, without any weapons. Sukune is considered as the father of sumo, but there are very few prints portraying this event Sumo bouts which ended without fatalities became a court pastime. Samurais practised sumo wrestling on the battlefield (Gozen sumo), as a result of which many terms connected with sumo are still in use today, such as the titles of the grades of fighter - Ozeki and Sekiwake, taken from military terminology. The sumo referee still carries the Uchiwa gumbei - the battle fan. with which the samurais used to give the signal to engage the enemy. The samurai sumo' contests which took place in the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries were so famous that they too were included among these historical prints.

The best known sumo contest depicted by the print artists was the fight between Kawazu Saburo Sukeyasu and Matano Goro Kagehisa, which took place in 1176 before the shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo during a festival held after a hunt. During this contest the weaker Kawazu overcame the stronger Matano. This impressed the Japanese greatly, and was even the theme of several plays. Kawazu was killed one day later, and his grown sons decided to avenge his murder. This is the theme of the Kabuki play 'Soga' - the name of the clan to which the family belonged. Katsukawa Shunsho depicted the event as it is performed on the Kabuki stage. In most of the prims Matano is seen clutching Kawazu's belt and lifting him off the ground. In a book written in 1763, the lightweight and inexperienced Kawazu is said to have ousted Matano from the ring as soon as the contest started. But Matano complained that he had not been prepared because he had tripped over a tree root. The referee Ebina Gempachi ordered a return fight. Matano grabbed Kawazu's girdle and lifted him up. Kawazu twisted his leg round Matano's leg, put his arm round Matano's throat, and prevented the latter from throwing him down. This grip is still known as Kawazu's Hold'. Matano grew weary, and Kawazu managed to tumble him. The artists of the Utagawa School, including Kunisada (1786-1864) and Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), also depicted this contest .

Many other components were incorporated into sumo from various sources. From the Kabuki sumo adopted the Hyoshigi - wooden sticks with which they rap together to Indicate the beginning of a bout and call the audience's attention to the ring. In the same way, customs were transferred from the sumo ring to the Kabuki, such as the Hanamichi. the route taken by the wrestlers on their way to the contest . The roof suspended over the ring is like that on the Shinto shrines, and the rope girdle decorated with paper which is tied round the waist of the Yokozuna (Yokozuna - 'horizontal rope'), the sumo champion is also derived from Shinto. The bow and the sword come from the samurai.

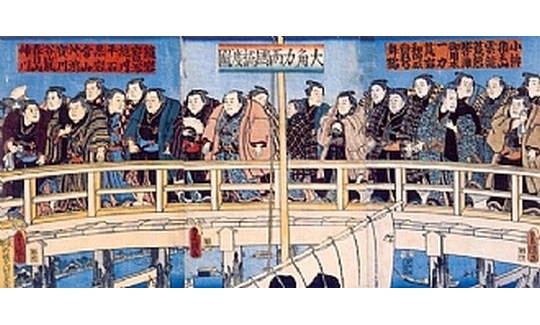

The contests were held in shrines which stood on the far side of the River Sumida to the East of Edo. so it was very common to see the wrestlers crossing the Rypgoku Bridge. In the seventeenth century a fee was paid for watching the fights. Some of the money collected was donated to the shrines, and some was used for maintenance (Kanjin sumo). The wrestlers had patrons, owners of estates (Daimyo) or samurais. In time, the wrestlers united into teams, and sumo became a professional sport, again charging a small fee to spectators. The names of the wrestlers are derived from natural elements - mountain, river, wind, valley, and they change each time a wrestler attains a higher rank. The status of a wrestler is the same as that of a samurai, and they have the right to carry two swords. The patron contributes the silken embroidered apron (the Keshomawashi) which b still worn for the ring-entering ceremony, the Dohyo-iri. On entering the ring, wearing their aprons, the wrestlers stand in a circle looking towards the centre. They dap their hands and raise their arms. This is often shown in the prints (see cover).

During the early years of sumo in Edo. the artists of the Torii school were authorized to design a table of wrestlers listing those of the same rank in separate squares. This was the Banzuke. the list of wrestlers according to rank, which is still in effect today. Their grades were established by assessing their wins and losses in the contests (Basho).

The demand for sumo prints increased together with increasing interest in the exciting contests which took place in the 1880s, such as that between Tanikaze and Onogawa. Tanikaze gradually rose through the ranks and achieved Ozeki in March 1781. By 1789 he was the principal Yokozuna sumo wrestler. Three wrestlers before him had received this title, so that Tanikaze was the fourth Yokozuna to wear about his waist the rope decorated with zig-zag paper, the Gohei. Tanikaze and Onogawa waged many contests against each other over the years. In 1782, at the age of thirty-three, Tanikaze was defeated by Onogawa after thirty-six successive victories. This dose contest between the two also aroused great interest in the sport among the Katsukawa artists, and sumo prints began to appear. The struggle between the two contestants divided the audience into two camps. Shunsho favoured Tanikaze, and his prints from the end of 1782 and the beginning of 1783 show his preference. Tanikaze's face is clearly shown, whereas Onogawa's is concealed or partly hidden. Shunsho's emotional involvement In promoting Tanikaze was so great that it eventually caused him to stop creating sumo prints. According to his ideas, Tanikaze should have become Yokozuna in 1784. though the Sumo Union only appointed him in 1789, together with Onogawa, due to commercial considerations. In 1785 there was a famine, due to which many entertainments were cancelled, including the sumo contests. In November 1786 the contests recommenced and Shunsho's last sumo print was published. The final bout between Tanikaze and Onogawa took place in October 1793, though Tanikaze continued to wrestle until November 1794, after which he fell ill and died of influenza. His death marked the end of the golden age of sumo at the dose of the eighteenth century. Onogawa retired in 1797. Tanikaze's place as Ozeki of the west team was taken by Raiden. Raiden never became a Yokozuna. At about that time a six-year old boy called Daidozan appeared in the sumo arena. Daidozan was an expert at performing the ring-entering ceremony and Shunei depided him in prints of which the background is covered with shining molecules of mica .

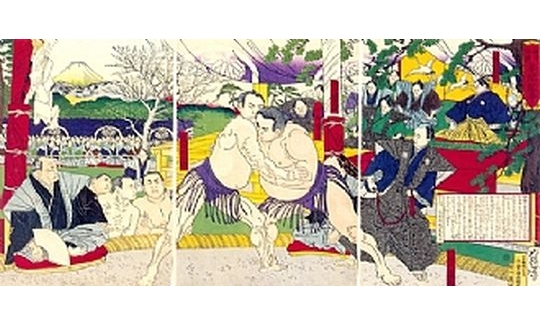

Shunsho was the first to create 3-fold prints. He used his woodblocks repeatedly, showing the same audience on each side panel of the triptych and changing the central panel according to the wrestlers in each contest. This re-use of the blocks resulted, in one instance, in a print of a sumo wrestler winning a fight and being watched in the audience by - himself!

In the prints by Shunsho's followers - Shunko, Shunei, and Shuntei (1770-1820) - the wrestlers appear with the crown of their heads shaven, a custom exclusive to the Yokozuna. Shund's prints were more neutral than Shunsho's. and he often used Shunko's blocks, adapting them to contests held in the 1890s by means of changing the faces and names of the wrestlers. In 1798 Shunei created a series of wrestlers wearing the apron, the Keshomawashi . These prints show one raised shoulder of the wrestler and the head Is turned at an unnatural angle. Shuntel created a similar series, and these prints were innovative in that the figure of the wrestler virtually filled the entire page .

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the artists of the Utagawa school, led by Kunisada. began working in this discipline which had previously been the prerogative of the Katsukawa artists. Kunisada, a pupil of Toyokuni (1769-1825), usually depicted historical events or Kabuki performances, so that when he began to make sumo prints his wrestlers often looked like Kabuki actors with long faces and wide open eyes. Kunisada was the first to add to his signature the word 'Oju' i.e. 'commissioned', when his prints were ordered by sumo enthusiasts. Like Shunsho, Kunisada made prints of the wrestlers crossing the Ryogoku Bridge in order of rank. Encouraged by Nishimura Yohachi of the Eijudo publishing house, he began in 1829 to use prussian blue paint in his triptychs, a major innovation. By the end of 1830 the publications of Eijudo and Kinshindo consisted chiefly of Kunisada's works, and he was considered as the foremost sumo print artist.

Toyokuni. Kunisada's teacher, died in 1825. Towards the end of his life Toyokuni modified his signature, writing the lower half of the word Toyo' in a zig-zag. His pupils Toyoshige (1777-1835) and Kunisada adopted this form, though Toyoshige, as his first pupil, was its rightful inheritor. Kunisada's use of the signature created friction in the Utagawa school. Initially, Kunisada simply used the name Toyokuni, which was confusing. Accordingly, Toyoshige added Kosotei' beside his name, to distinguish his work from Kunisada's. Nor did all Kunisada's prints published by Eijudo include the name Toyokuni. presumably because he was aware that the appellation really belonged to Toyoshige.

Eijudo published about half of Kunisada's sumo prints between 1828 and 1843, ail of them simply signed 'Kunisada'. However, this was of little help to the less experienced Toyoshige. Kunisada's talent and expertise greatly increased the popularity of his prints in the 1830s. The prints of the first Utagawa Kunisada can be identified by the strange anatomical construction of the wrestlers' thumbs, which look more like lingers. Toyoshige's prints can be distinguished from those of Kunisada by his finer portrayals of faces and bodies, resembling In this respect the wok of Shunsho. He was mainly occupied with depicting sumo wrestlers wearing the Keshomawashi. though no prints by him of wrestlers in action are known. Toyoshige died in 1835. and the Toyokuni family formally gave Kunisada the right to adopt their name in 1844.

As with the Katsukawa school, the Utagawa artists who had been accustomed to making Kabuki prints had (difficulty in depicting the wrestlers' naked bodies and their faces without cosmetics. However, in the picture of sumo wrestlers led by Onimatsu and the Kabuki actors led by Nakamura Shikaku. sitting together in a pleasure boat crossing the Sumida River, a different treatment can be seen . The wrestlers' faces are round, whereas the actors' faces are long. The wrestlers are portrayed naturally, whereas the actors look as if they are still on stage. In this print Kunisada makes brilliant use of Prussian blue together with orange. Since blue and orange are complementary colours, the eye moves from one to the other. Traditional Japanese prints are known for their flatness and lack of perspective. The complementary colours reinforce that flatness, having the same tone. This effect had a great influence on the European Impressionists, especially on Van Gogh. Next to his signature Kunisada writes 'Okonomi ni Tsuki'. indicating that the print had been commissioned by an important personage. In the 1830s Kunisada adopted Shunsho's triptych compositions. In the centre we see the sumo wrestling bout, and the audience appears in the side panels.

Mizuno Tadakuni was appointed at the end of 1841. as advisor to the Shogun leyasu. Amongst the reforms he instituted was a prohibition of sales of prints of the entertainment world. Fortunately he did not include sumo prints in this category, as a result of which many artists began to create them. In addition, artists were forbidden to use more than seven colours, but overcame this by means of printing one colour on top of another.

Many of Kunisada's prints from that time show the new Yokozuna Shiranul. especially his aggressive entry into the ring. Apart from Shiranui, who is shown with one foot raised at the climax of the ceremony, and the Yotozuna's attendants on either side, there is nothing else to be seen. Other prints of sumo contests show the wrestlers In all three sections of the triptych, with referees on the right and the left all in close-up. The use of the three panels as one unit originated with Shunsho. The single print close-ups originated with Shunko. and the threefold dose-up prints of wrestlers come from Kunisada. who even made a triptych of the contest of Matano versus Kawazu . Perhaps because this was a historic bout Kunisada allowed himself greater freedom of expression. The ring Is not shown, and the print has a monochromatic background. The scene is daring. Kawazu has thrown Matano, who is falling headlong, while the referee Ebina is holding his fan in the rear. In the 1850s Kunisada also created prints of a single wrestler during the Shikiri - the challenge, either with a referee or completely alone. In fan it was the Katsukawa artists who laid the foundations of sumo prints - the triptych and the single wrestler covering the entire print. Kunisada's innovation was the depiction of monumental wrestling matches In which the wrestlers face each other in all three sections of the triptych. This composition was borrowed from him by Kuniteru (1808-1876).

In February 1844 an official statement appeared on Kunisada's prints - 'Kunisada aratame nidai Toyokuni' - Kunisada has changed his name to Toyokuni the Second'. For this reason researchers have considered him to be Toyokuni II. whereas in actual fact he is Toyokune III. The phrase can be seen, for instance, on a print of Ikazuki standing against the background of his hand print. This is explained by Kunisada's only receiving permission to adopt his teacher's name In 1844, and not in 1835, when Toyoshige. Toyokuni s first pupil died; or that Toyokuni s widow died In 1843. at which time the family rescinded their objection to Kunisada taking his name. In 1846 Kunisada also added his artistic names Kochoro and Ichiyosai to his signature.

In 1845 the rising star of sumo, Koyanagi, beat Shiranui several times. In 1852 he received the title Ozeld. and in 1854 he appeared before Commodore Perry. Koyanagi. who was the subject of many prints, left the sumo ring in 1856 . Another wrestler who frequently appears is Hidenoyama, who replaced Shiranui as Yokozuna In 1845. Hidenoyama was quite short - 170 centimetres, weighing only 135 kilograms. and his short arms and legs made it difficult for him to get a grip on his opponent's belt. Kunisada depicted these new champions, and from 1841 to 1847 he created some one hundred and fifty sumo prints - the same number as Shunei made in his lifetime.

As of 1848 prints by younger artists, pupils of Kunisada and Kuniyoshi. began to appear. Among the artists were Kuniteru, Kuniaki (active 1850-1860), and Yoshitora (active 1850-1880). However, no new ideas about composition were evident in this flood of prints, which once again began to depict the events in the ring in greater detail, and in which the influence of the western concept of anatomical construction is also evident.

After 250 years of peace and eolation Japan was strategically unprepared to reject the demands of Commodore Perry on March 24th 1854, that the Japanese ports be opened. Discussions with the Americans took place at the small seaside village called Kanagawa. which is today Yokohama. In accordance with tradition, the Japanese offered sacks of rice to the President of the United States, each sack weighing 55 kilograms. These sacks were loaded onto ships by sumo wrestlers wearing their Mawashi. each of them carrying three sacks at a time - a pacific demonstration of strength. The American soldiers, who did not understand the meaning of this gesture, saw the wrestlers as threatening beasts. Such an event might have been an interesting new theme for creating prints, but no artists were allowed to be present, and very few examples exist.

In the 1850s many sumo prints appeared without the name of the wrestler, making them difficult to identify. The Yokozuna wear the apron, but their heads are not shaven as in the past. The apron is the only source of possible identification of the wrestler, or of his patron. In 1859 Kunisada reverted to creating Kabuki prints, and continued till he died in 1864. During that period several Important events occurred in the sumo ring, in some of which Yokozuna Shiranui II and Unryu participated. Prints of these were made by Yoshitoshi's (1839-1892) pupil Yoshimori (1830-1884; page 31). Kunisada and Shunei continued to make prints for more than thirty years. Shunei's main contribution was to develop the ideas of Shunsho and Shunko. By the time Kunisada began making prints there was virtually nothing left for him to add. but he did manage to instil a breath of life into the subject.

The sumo prints in this exhibition are all from the collection of Goran Flyxe of Stockholm, who lived in japan from 1971 to 1975. His love of the sport and the art induced him to collect Japanese Ukiyo-e prints on this subject. He meets people from all over the world who, like himself, love sumo and the art which accompanies it. He has now been collecting for twenty-five years, and still continues to search for interesting new examples. Mr. Flyxe's collection concentrates mainly on prints of the Utagawa school of the nineteenth century, but also includes a number of Katsukawa prints from the end of the eighteenth century.

To read about The Japanese National Sport click here