Originally, the netsuke was a carved and embellished clothing accessory that was tied with a cord to other items known as sagemono (hanging things). These might include inro (containers for seals and/or medication), tobacco pouches, purses, or boxes for writing implements. The traditional Japanese garb, the kimono, has no pockets, and is fastened with a broad sash around the waist, and all these containers were attached to a cord that was inserted underneath the sash. The netsuke, attached to the other end of the cord, hung on the outside of the sash, and was intended to secure the items from slipping off the cord.

As is evident from the meaning of the word netsuke (ne - root; tsuke - fastening) this was initially a very simple item - a piece of root, bamboo, or bone with a hole in it, through which the cord was threaded. However, it soon became an object for artistic endeavour, a tiny sculpture that embodied every conceivable aspect of life. The netsuke was used by men of all ranks as of the 16thcentury, and was most prevalent during the Edo period (1603-1868).

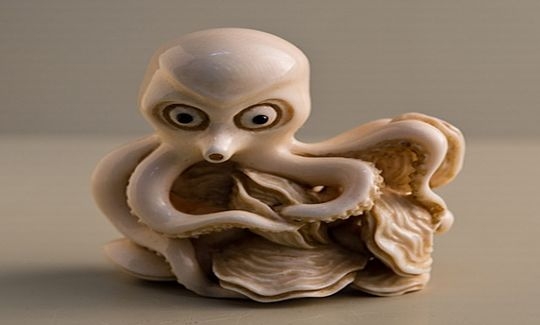

Netsuke are made of various materials. These include: wood - Japanese cypress, box, cherry, plum, and others; ivory, whale and hippopotamus teeth, and the fangs of the wild boar. There are figurines made of horn, bamboo, bone, semi-precious stones, tortoiseshell and metal. Materials said to have medical properties were also used - the jawbone of a particular species of whale to reduce fever; stag antler as an antidote for snakebite. One surface of a netsuke of this type was left undecorated so that it could be scraped, and the medication was made from the powder thus obtained. The artist chose his material according to its availability in the district where he lived, and according to its adaptability, weight, and strength. Netsuke were created by means of different techniques - carving, relief, turning, engraving, filigree, casting, stamping, lacquer, ceramic, inlay, paint, and this was considered as a craft for men. Thirty to sixty days were needed to complete a single netsuke.

The earliest netsuke artists sculpted figures from the world of religion - most of their subjects were deities, fabulous creatures who had become deified, demons and ghosts. But ‘real' and demonic creatures from the world of the living were also represented, as well as those connected with folklore.

In the Edo period, subjects were also taken from daily life, having no connection with belief or religion - depictions of people of all ages going about their various occupations - artisans, travellers, acrobats, children, monks, musicians, actors, people bathing or sleeping, people with their pets or sitting idle.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), the kimono, worn by men and women alike, was worn exclusively for special events and ceremonies, and was replaced by western-style clothing for everyday. This gave rise to the disappearance of the netsuke and other items that had previously been made by the finest Japanese artists, for whom they were a source of income. As soon as this income ceased, the artists turned to making items for export. Foreigners who came to Japan began to trade in netsuke that had been discarded, and these found their way to Europe and America with other items. In the 1970s, collecting netsuke became very popular in the West.

As the demand for Japanese artifacts increased, the artists also began to make large numbers of complex and detailed decorative items, carefully maintaining their high standard. Netsuke carvers made okimono figurines (okimono: placed things) of ivory and boxwood that were very like netsuke except that they did not have the himotoshi - the hole in the back or base of the netsuke for inserting the cord. Okimono subjects include: samurai, mythological creatures, pretty girls, animals, birds, fishermen, peasants and farmers, craftsmen, children playing, and scenes from everyday life.

The technical proficiency and exactitude of detail, the Japanese artists' aspiration to perfection, make these works of art completely aesthetic, evident in these tiny figures represented so realistically, with humour and a wonderful vitality. Perhaps the artists' intention was not necessarily to create humorous articles, but many of the figurines do present the comic elements of everyday life. As a rule, this is not achieved by exaggeration, grotesquerie. It is, rather, their naturalness that brings a smile to our lips.

The Toister Collection was donated to the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art in September 2012. Many netsuke in the collection are from the Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa (1926-1989) periods. Some were carved by Japanese artists, others by Chinese artists, in order to meet the demand in the western market.