The shrines of Japan are used for the ritual ceremonies of two religions - the Shinto and the Buddhist. The many temples scattered throughout the length and breadth of the country are familiar sights, and Japanese artists have always found, in them and in the life that goes on around them, a subject for personal expression. The wooden buildings, large and small, with their wooden or tiled roofs, are constructed without nails or screws. By means of careful joinery of the beams, the Japanese have made many buildings, among them the Todaiji Temple at Nara, the largest wooden building in the world. The Japanese carpenter-craftsmen of today are considered as national assets.

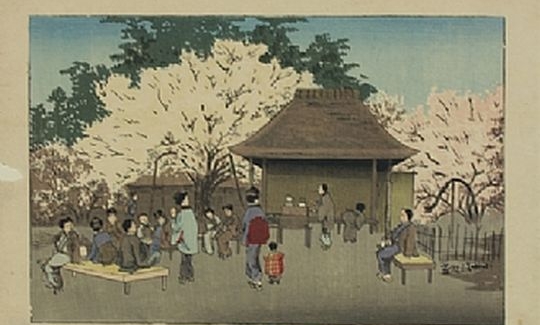

Shinto, the original Japanese religion, believes in the existence of manifold deities who are to be found in all aspects of nature and the universe, and who embody all these aspects. For Shintoists, every natural manifestation is sanctified. Belief in these innumerable deities led to the construction of many temples. Shinto shrines are called ‘Jinja'. A believer who hopes to receive the gods' blessing must visit them, offer tributes, and participate in the various rituals. The original Shinto shrine was a sacred natural site, enclosed either by a rope on which were hung pieces of white paper, or approached by a ceremonial entrance gate. The shrine itself is a precinct with a wooden sanctuary and several other buildings where ceremonies, prayers, and ritual offerings take place.

Temples vary greatly in construction, in size, architecture and organization of the buildings. The precinct is rectangular, and is surrounded by a fence which sets it apart as a holy place. In the rear stands the Honden, the sanctuary itself, which contains the Goshintai, the sacred object inhabited by the virtue of the deity - the Kami. Sometimes the Goshintai enshrines more than one deity. The Haiden, the hall of prayer and worship, lies in front of the Honden, sometimes concealing it. In front of the Haiden, the Shinto priest conducts the rituals, and the worshippers offer their tributes. Sometimes a covered pathway connects these two buildings. Believers announce their presence at the shrine by clapping their hands and ringing a bell which hangs from the roof-beam of the Haiden to attract the gods' attention. Worshippers slip their contributions into a large rectangular wooden box which stands outside the Haiden. The ordinary believer cannot enter the Haiden or the Honden, and indeed, even the Shinto priests can only enter them on special occasions. They are only permitted to live in the very large precincts. The smaller shrines usually comprise one main building with the Haiden in the front and the Honden at the rear. A natural shrine, such as a mountain, hot springs, or a waterfall, has only a very small building, the natural object itself being the Honden.

At the entrance to the Shinto shrine stands the Torii, the characteristic gateway constructed of two uprights, across which are laid two horizontal beams. A path, which sometimes passes under several of these gates, leads to the Haiden. Near the path, not far from the Haiden, stands the Temizawa, a pavilion for washing the hands and mouth for ritual purification. At the entrance to the shrine, or on either side of the steps leading to the Haiden, sit two stone lions (Komainu: Korean dogs), guardians of the place. On festival days, a heavy straw rope, the Shimenawa, is hung at the entrance, with pieces of white paper dangling from it. There are other buildings in the precinct - store-rooms, ritual implements, a hall for preparing food for offerings, and a place for selling amulets. Sometimes, as at Ise, there are several shrines which are identical. Sometimes branches of shrines dedicated to the same deities are to be found elsewhere. There are, for example, 30,000 shrines in Japan consecrated to the Rice God, Inari.

In the 6th century CE, Buddhism reached Japan from India, by way of China and Korea. Buddhism did not replace Shinto, and both religions function side by side, the majority of the Japanese adhering to both faiths. For this reason, Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines often stand together on the same site. Essentially, Buddhists believe, not so much in deities, as in the rebirth of the soul. However, as the religion developed, many gods came to embody its doctrines. Statues of these gods stand in the Buddhist temples, providing a focus for the rituals. The monks also live in the temples.

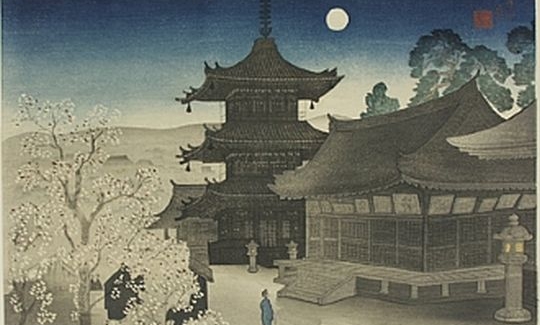

Buddhist temples are known as ‘Tera', and there are some 77,000 of them in Japan today. Usually they comprise seven structures. The pagoda, which is the most important, is a tower of five or seven storeys, which contains the sacred relic of Buddha. Originally, the pagoda was built in the centre of the temple precinct, with other halls beyond it and on either side. In the Horyuji Temple (built in the 7th century CE) a main hall houses statues of the Buddhist deities, and here, beside the pagoda, the ceremonies are held. In other temples, this hall is the central feature, and the pagodas on each side of it are purely decorative. In the Kofukuji Temple, completed in the 8th century CE, the pagoda stands beyond the sacred precinct. These variations indicate the modifications in the concepts of the faith, and the development of Japanese styles of architecture.

Another important building is the lecture hall, where lectures are given to large audiences of monks. This hall, which is situated behind the main hall, was formerly completely separate, but was gradually moved closer, and a covered walkway now connects the two. This hall is spacious, sometimes even larger than the main hall, and both these buildings are single storeys covered with a roof. In the past, two corridors extending to right and left from an inside entrance surrounded the main hall and its approaches. In the Nara period (710-784 CE) these temples were surrounded by a wall with entrances on all sides, each with its own name. The southern gate was the main entrance. These gates are usually two storeys high. Other buildings in the temple precincts are the bell hall, the archives for the sutras, the monks' dormitories, and the store-rooms.

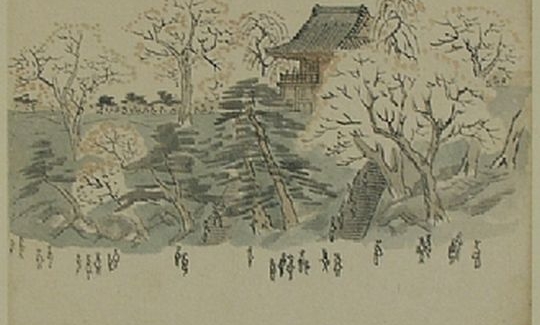

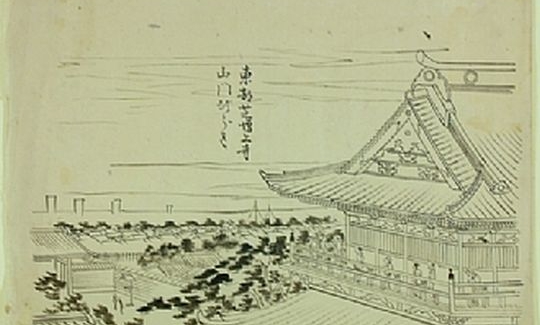

Exhibited are some forty prints and drawings, in all of which the temples of Japan are depicted. They present various temples as they were seen in the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century.