Noriko Yanagisawa was born in Hamamatsu, a city in the Shizuoka Province of Japan, in 1940. At the National University of Arts and Music in Tokyo, she studied oil painting for her first degree, and went on to specialize in etching techniques for her second degree. On completion of her studies, she was awarded the Japan Print Association Prize, and became the youngest member of this group, which is regarded as a great honour in Japan. In 1971 Yanagisawa went to New York, where she remained until 1975, creating works by the printing technique. This opened the way to the beginning of her international career.

As of 1969 Yanagisawa has had many one-man exhibitions in Japan, The United States, Korea, Portugal, Italy, and other countries. She also participates in group shows world-wide, and her works are included in museum collections in Japan and the United States. The present exhibition has reached the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art after being displayed in Bulgaria.

Several motifs, among them the human body and the earth, are central to Yanagisawa's work. The earth is the locus and source of our being, and man's doings and works on earth are, without doubt, the focus of Yanagisawa's interests. The human figure is usually naked, doll-like. Strips of fabric are wrapped about it, like winding-cloths. It is headless, because Yanagisawa has no interest in the individual, but rather in universal man. Since she has no aspirations to creating a personal drama, she has selected the etching technique as a universal form of artistic expression. For all of that, everything is viewed through her own personal, private vision.

Another motif which frequently appears, and is also connected with humanity, is the felled tree stump, with its roots protruding from the earth. In the compounds of many Shinto shrines there are ancient trees growing. According to belief, they provide a resting place for the gods descending from the mountains, especially in the spring, to fertilize the fields, for which reason they are sacred. The destruction of sacred trees is one of the crimes of modern man against the earth. The tree stumps and torn branches in the prints are the artist's protest against the uprooting of the trees and the destruction of the Shinto shrines. Yanagisawa warns against the rejection of the traditions and culture of Japan by the modern age because of the transformation of nature into cities of concrete and iron. Perhaps the headless man also implies lack of roots, culture, and tradition.

Yanagisawa believes in maintaining tradition, and not in its destruction to make way for the new. For this reason I decided, together with the artist, that her exhibition should be called ‘Mori'. Mori has two meanings in Japan, - ‘forest' and ‘Shinto precinct'. Although these are written with different Chinese ideograms (Kanji), they sound identical. Perhaps it is not by chance that they are the same, demonstrating how closely the Shinto belief is allied to Nature.

The fossils appearing in the prints, both on the human bodies and on the rocks of the altars are ‘prints' created by Nature. The cloth strips wound about the bodies like winding-cloths, and the fossils are symbolic of the wheel of death and rebirth, and thus of time itself. The art of the Far East is influenced by the Buddhist concept of a world in flux, and this concept has aesthetic value in Japanese art. The moment of human realisation of the world as change is accompanied by the ‘sadness which is in things' (mono no aware), but also by aesthetic pleasure. Beauty, according to this concept, is to be found in the moment of fading, and not in the full blossom. Death too is considered beautiful, an expression of temporality and change. The trees uprooted by man in the force of their maturity, before their life-cycle is completed, are another conspicuous and melancholy motif in the aesthetic of Yanagisawa's works, and emphasize their Japanese quality.

In classical western art, the concept of beauty is concentrated on the perfection of the human form. Conversely, in the oriental concept, man is not regarded as the centre of the world. Ideal beauty is to be found in all of nature, rather than in man alone. Man is part of nature; and nature is not merely a background for man, but a positive entity in its own right. Yanagisawa's works move between these concepts, being neither completely figurative nor completely abstract. The path taken between them is perhaps indicative of the artist's wish not to reach a tried and tested definition of style, and thus to make room for displaying many possibilities.

The motifs in Yanagisawa's works - the human figure, fossils, tree-trunks - all are of equal significance. This sense arises from their juxtaposition. Yanagisawa does not differentiate one motif from another by means of chiaroscuro, or by using strong colours against a background. This technique creates a sense of flatness. Relating to the paper as a two-dimensional surface, and the reluctance to create a three-dimensional illusion undoubtedly derive from the traditions of the Japanese aesthetic.

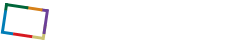

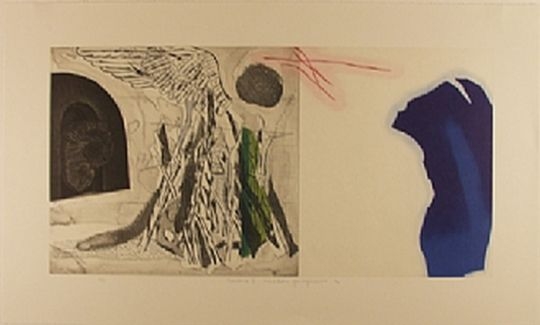

Some of Yanagisawa's prints are divided into two unequal sections. In the larger section, actuality is represented, while the other, which is almost bare, is symbolic of the potential. The recurring motif of the wing, either against the empty background or in the picture itself, symbolizes the possibility of flight to another universe, or to a new reality. In other words, the wing is a symbol of Nature's freedom to create a new reality in the future. Yanagisawa uses primary colours on the bare areas of her works - blue, red, and yellow - which sometimes extend into the representation of actuality. In the latter, she also compounds the primary colours, employing green and orange and many other hues and shades. The primary colours on the bare areas are the building blocks from which Nature derives her manifold forms. Nature's potential is to be found in these basic elements, but the results derive from the freedom to combine them into new creations, just as the artist is free to create a broad spectrum of unlimited variations from these same three primary colours.

Yanagisawa calls some of the works in the exhibition ‘Fragments'. These fragments are like the Japanese haiku of seventeen syllables contained in about five or nine words, and without any conjunctions. These verses are fragments of an actuality which we comprehend both directly and intuitively, combining them into a clear picture of a universal reality.