Traditional ukiyo-e prints (ukiyo-e: pictures from the Floating World) were among the most important artistic achievements of the Edo era (1603-1868), which began to decline with the death of the artist Ando Hiroshige in 1858. Contributing factors were the opening of the gates of Japan to the West in 1853 and the Meiji Restoration (1868), which led, among other things, to new artistic revelations. At this time, Japan was particularly exposed to the influence of European art, although there were those who recognized the need to preserve their traditional art.

Most of the artists in the latter half of the 19th century were pupils of Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Kunisada, and Ando Hiroshige, though the younger artists employed brighter colours and dominant shades, such as red or purple. This riot of colour was in total contradiction to the lyricism of the traditional works of the print artists, and the people of the time accordingly saw them as "westernized" in style. After a short phase in which Japan was flooded with such prints, some Japanese artists, among them Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) began to seek an artistic compromise between traditional and western-influenced art. This artistic movement was called Shin-Hanga (New Prints), which was active mainly in the first thirty years of the 20th century.

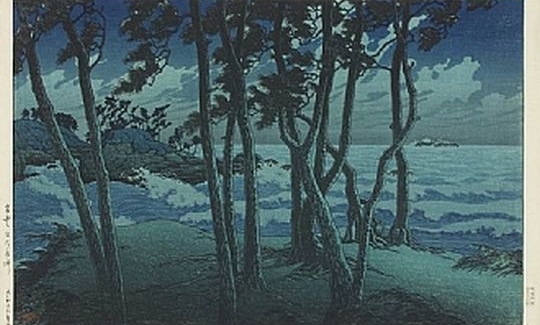

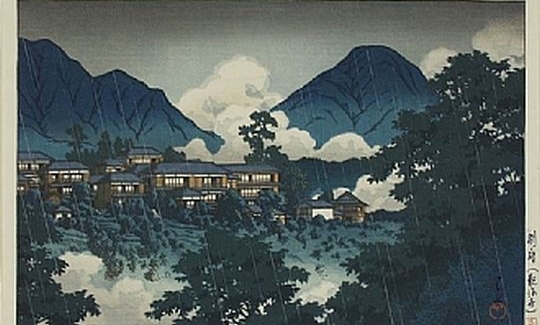

Hasui, encouraged by Watanabe Shuzaburo the publisher, was one of the best-known traditional artists who tried to revive this art and, at the same time, develop the realistic trend which had already begun at the end of the 18th century. His works from the beginning of the 20th century, including those in the exhibition, make it apparent that he succeeded in integrating in his prints the foundations of the new European aesthetic of his time. This integration of such western concepts as perspective and realism arose from the desire to revive the moribund art of the print. Realistic representation or photographic detail of landscape in the western sense were new to Japan, and Hasui made a point of creating such realistic illusions as snow, or reflections in the waters of a river or a lake. Thus his prints mark the passage from the traditional to the modern Japanese print. They were, nonetheless, created by the traditional method - he drew the picture, the carver prepared the block, and the printer printed the work, which was then marketed by a professional publisher.

In his works, which were mainly sold to foreigners, Hasui succeeded not just in preserving the art of the ukiyo-e, but even in transcending it, both artistically and technically. However, this sudden adoption of a new culture vitiated the traditional art of its spirit and values in attempting to imitate nature and achieve absolute realism. Thus, while the European artists were seeking ways to escape from their realistic tradition by turning to the Japanese print, the Japanese artists were influenced by western realism and perspective - just those techniques which the western artists had abandoned. This was the end of the traditional art of the Japanese print.

Kawase Hasui created some four hundred and sixteen prints during his lifetime, most of which were published by Watanabe Shuzaburo. In the fires which occurred in 1923 following the earthquake which destroyed Tokyo, all the wooden blocks of his prints were lost. All the prints which are stamped with a round seal enclosing three drops of water (sui) were printed by Hasui after the earthquake.

In 1956, Kawase Hasui received the title "Living National Treasure", as one who had preserved the art of the traditional woodblock print.