One of the significant characteristics of modern industrial design is the absence of national boundaries. Today, designers worldwide are concerned with the balance between artifacts designed by man and natural objects designed by nature.

"Essentially, modern design tries to integrate, by means of modern technologies, new and natural materials to create a balance of harmony and comfort in everyday living. Thus, lifestyle is the inspiration for a well-designed article. The form and colour which constitute the beauty of an object are certainly important elements, but the article has no meaning if it is purely decorative. However, even articles which are not in daily use should be pleasing. The designer must, above all, examine the mores of his era in order to create worthwhile objects which will also enrich our spiritual world" says Toshiyuki Kita.

He was born in Osaka in 1942, and completed his studies in industrial design at the University of Naniwa in 1964. Since then, Toshiyuki Kita has been occupied with product, space, and environmental design. He opened his design studio in 1967, and in 1969 he began working in Milan as well as in Japan.

Kita presents many international design exhibitions. On the tenth anniversary of the Pompidou Centre in Paris he showed "Ceremonial Space" (1987). In 1988 he exhibited in Vienna and in Milan, in 1992 in Helsinki. Two of his creations have been selected for the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and, after his exhibition "Cha a la Carte", of pewter tea ware, thirteen of the items were acquired for the collection of the French Museum of Modern Art.

Over the years Kita has received many awards, both in Japan and abroad, including the Japanese Association's Award for Interior Design in 1975; the prize of the American Foundation for Industrial Design (1983); and the Delta d'Oro Prize from Spain in 1990. Kita is also a member of judging committees for design competitions worldwide.

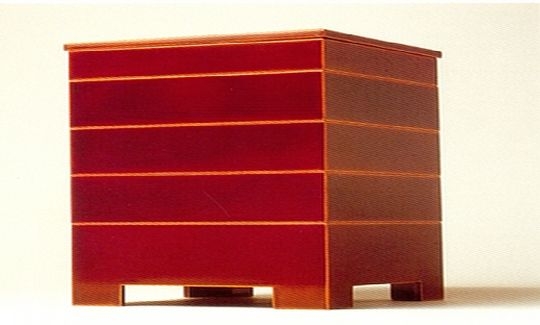

Toshiyuki Kita designs functional modern articles of lacquer and Japanese paper, in order to preserve these traditional Japanese crafts. These two materials, which were already used in Japan more than a thousand years ago for making objets d'art and practical artifacts, are on the verge of redundancy, and only a few Japanese artists continue to preserve the knowledge required for their preparation. Kita has known about paper and lacquer articles since his childhood. In 1968 he began to look into the possibilities of making lacquer wares, and in 1971 he started creating modern Japanese paper lighting fixtures according to the spirit of the time. In his various designs, Kita succeeds in reviving the traditional Japanese aesthetic of economy and simplicity. The synthesis of this aesthetic tradition and modern design creates a new product, the like of which has never before been seen, but which nevertheless retains a deep sense of tradition. Although the articles are made of traditional Japanese paper and lacquer, they do not necessarily seem Japanese. By the same token, they do not seem modern according to western eyes. The design of these dishes and lamps embodies the artist's enduring respect for the traditional materials.

Lacquer and paper are derived and produced from simple natural materials, until they culminate in high quality, specialized objects of beauty. Paper is made by working the inner bark of a tree, usually the Kozo tree, one of the mulberry family. From this inner bark a pulp is prepared, and then spread in a layer on special mesh frames. Today only a few paper-making workshops continue to survive. The destruction of nature, lack of younger paper craftsmen, and other problems have placed the traditional paper industries in crisis.

Kita is trying to integrate traditional Japanese paper into new designs, in conjunction with paper studios throughout Japan. He uses this new paper mostly for fashioning lampshades - designing lamps that display the paper's special qualities. The light filtering through the texture of these lamps spreads a soft glow, and generates an atmosphere of serenity and meditation.

Covering dishes with lacquer and polishing them times without number is a long process requiring practice, and has been passed down from generation to generation. The number of lacquer-producing trees in Japan has greatly diminished. Since each tree only gives a small quantity of lacquer, objects made of it are very expensive today. Thus, only a few privileged people can allow themselves to use genuine lacquer ware, and then only on special occasions or for the tea ceremony. With the aid of modern technology, cheap plastic products imitate lacquer, and are very popular for daily use. However, as Kita says "These articles do not have, of course, the natural beauty that glows from the surface of real lacquer".

In Japan they believe that each tree has a soul. "The Japanese craftsmen used the tree's soul, breathed the human spirit into it, and created a synthesis of the two", Kita says. "That's why the crafts of lacquer and paper express a balance between nature and the wisdom of mankind."

Today, when we are surrounded by the hi-tech environment which generates coldness, lacquer and paper products give us a sense of warmth. Toshiyuki Kita sees these crafts as a priceless heritage, inspiration for the many quality articles he creates by means of modern technology.