In the year 1603, after a long and bloody civil war, the Tokugawa Shognate came to power in Japan, a military rule that lasted more than 250 years. The Edo period (1603-1868) was a time of tranquillity and economic prosperity in a country which was almost completely cut off from the rest of the world. There was a hierarchy which enforced political and social order, creating a division between the upper class (the samurai) and the lower classes - peasants, craftsmen and tradesmen. Social status was inherited, and it was not possible to move out of one's class, not even through marriage or other connections. Those who married women from a different class were sentenced to death.

This period of peace and political stability was conducive to making some of the samurai, the highest rung in the social ladder, idle, and the economic superiority of the aristocracy declined. The tradesmen, craftsmen and workers who lived in the big towns became "townsmen" (chonin). Apart from the rigidity of the feudal system, the sense of security led to developing trade, and reinforced the status of the merchants, even though the ruling powers considered them as the lowest stratum of society. The guiding principle in their regard was "not to let them live or die" (ikasazu korosazu), and many edicts were imposed on them. For example, they were forbidden to wear expensive clothing made of coloured silks, or to build houses with more than two storeys. But the prohibitions imposed on the lower classes in order to maintain the hierarchy did not prevent them from acquiring wealth, and this wealth gave rise to a new city culture, a new artistic taste - the "Floating World" (Ukiyo). Ukiyo was originally a Buddhist expression for this transient world full of suffering, but at the beginning of the Edo era the phrase took on a new meaning: the world of the moment, of joy and pleasure which disappear like a gourd floating on the waves of the sea. The Floating World was an illusion, the life without care of the fashionable, refined and sophisticated nouveaux riches. Education in earlier times had been the privilege of the upper classes, but now it spread throughout the lower strata of society, to the peasants and craftsmen, and to many of the merchants. For the first time, the lower classes of Japan were the arbiters of cultural style.

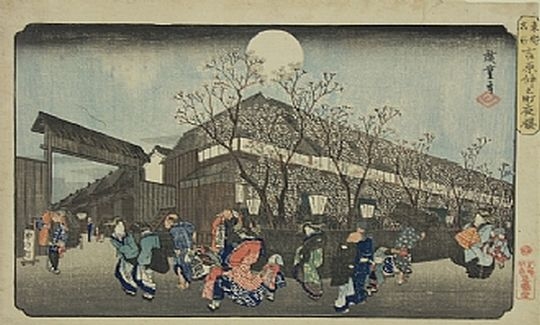

The art depicting this "new" world was the Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World), illustrating the leisure activities of the town-dwellers who had time and the means for enjoyment and luxuries. Initially, the ukiyo-e paintings were influenced by the classic styles of the Kano and Tosa schools. The artists began to portray scenes of life in the pleasure quarters - the visitors, the boats plying between the upper reaches of the Sumida River and the pleasure quarter, the passersby studying the prostitutes in their wooden pens, and the teahouses. By the end of the Edo era, this art was the universal culture of Japan. The techniques of woodblock printing were developed at the same time, offering the possibility of an almost unlimited number of reproductions from a single block. Obviously, the ukiyo-e artists utilized them for portraying the pleasure quarters of the big cities, the brothel areas and the Kabuki theatre, places where the townspeople could enjoy themselves and "show off" their wealth. Unlike the traditional Japanese art which was only accessible to the aristocracy, the woodblock prints were available to ordinary people, whose preferences were for those depicting the pleasure quarters or illustrating the guidebooks to these places. In the Edo era, when the pleasure quarters began, anyone in the entertainment business - prostitutes, actors and the like - were "classless", "non-people" (hinin), social pariahs.

Paintings of the pleasure quarters and their inhabitants by famous artists are the main source for understanding this world and its women. The routes to the quarter have been depicted - by boat, palanquin, horse, or on foot; the clothing, the teahouses, the streets and the brothels; and, above all, the pleasure girls in these districts, which became the entertainment centres of the cities of the mid-17th century. Originally they were painted on silk or paper which were then made into long scrolls, but so great was the demand that they started making woodblocks, from which innumerable reproductions could be printed and sold at popular prices.

The ukiyo-e of "beautiful women" were known as Bijin-ga, and portrayed women in all kinds of circumstances. Those of the high-ranking courtesans have little relation to personal characteristics, so that the name of a particular courtesan is often written on the picture, together with that of her brothel, or the emblem of that house appears on her clothing in the print or painting. Such works certainly made these women from the lowest stratum of society famous. Each artist managed to convey the lines of the body, the personal traits of each courtesan, their hands and features, in spite of their anonymity. In the paintings of Suzuki Haronubu (1725-1770), for instance, the faces are blank, expressionless, the hands and feet are tiny. By comparison, Isoda Koryusai (1765-1780) was one of the first to depict these women more realistically.

In the second half of the 18th century, the market for art works in Edo was at its peak, and the classic aristocratic tradition no longer had the same impact on the ukiyo-e. In the paintings of Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815), who left his impress on the 1880s, it is evident that he had abandoned the idealization of earlier artists, and depicted the women more naturalistically.

The high-ranking courtesans were usually represented in art and in the Kabuki theatre as aristocratic women, living a fine, elegant life. They were fully clothind in exquisite, beautifully ornamented kimonos, but were never depicted naked, and their hair was carefully and elaborately dressed, in hairstyles that help us to date the paintings. In the 17th century, for instance, a single comb decorated with a ribbon was set in the hair. In the mid-18th century, the hair was swept high, secured with three combs and seven decorated tortoiseshell pins. Later, the number of pins and combs was increased to twelve, with additional ribbons. The artists' meticulous representation of the hairstyles and clothing turned these women into "fashion models".

These courtesans were often portrayed in art as a sort of parody (Mitate-e: "comparable pictures") of the ladies of the court in the Heian era - perhaps because they wanted to equate them with a pseudo-cultural aristocracy. In a painting by Miyagawa Choshun

(1683-1753), a room contains elaborately decorated scrolls or folding screens, as in the castles of the nobility. In Katsukawa Shunsho's (1726-1792) works, and in those of Ishikawa Toyanobu (1711-1785), Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), and others, the women are reading, writing letters, singing, playing music, enjoying other classic occupations such as calligraphy or painting - all the activities of the educated Chinese, indicating the high level of education of the courtesans. They are nearly always fully clothed. A courtesan whose long black hair flows across her shoulders is equated with the aristocratic ladies of the Heian era.

So much elegance creates the illusion that the courtesan had nothing to do with the brothel. Ando Kaigetsudo's (ca. 18th century) painting presents the courtesan as an ideal of feminine beauty, and one must study the little hints given (e.g. in the classical literature) in order to understand the work. Unlike submissive married women, concerned with the household, bearing children, making ends meet, the courtesan had to be romantic, beautiful, refined, cultured, sexually adept. All these qualities are apparent in art.

In the paintings and prints of the time, the women of the pleasure quarters seem to be taller than they actually were ("extension" was the technique used by artists to make their subjects more impressive), and their faces are depicted according to the prevailing concept of beauty. It must be remembered that concepts of beauty differ from culture to culture. Thus, for example, blackening the teeth, which was customary at various periods in Japan, may not seem exotic or attractive to us.

For the men of that time, the prints were a sort of advertisement of idolized beauty and sexuality, and for the women they were the fashion plates of the period. Unlike the geisha or the women of propriety, the courtesan is easily identifiable in prints and paintings: the sash securing her kimono is fastened in front, instead of behind. The width of the sash is an indication of the period because, from the middle of the 17th century, it was very broad, about twenty centimetres, whereas at the beginning of the century it was only half as wide. The courtesan's robes were very elegant, and some were even hand-painted by famous artists. The details of dress and hairstyles also differed for the geisha, whose kimono was usually plain, with a deep opening at the nape of the neck. In her hair she wore a single comb, and two coloured hairpins, one long and one short. Her face and throat were whitened with a special cosmetic powder, and she wore high clogs (Geta) on her feet. The variety of fashions, kimono designs, how the sash was tied, the hairstyles were frequently invented by the kabuki actors who played as onnagata and also influenced the fashions of the quarter.

In the woodblock prints, the embroidery or the special designs were accentuated by a special technique of applying pressure while printing, creating a kind of relief in the desired areas, and also by overprinting in different colours. This gave an illusion of real cloth and/or embroidery. As of the 18th century, the courtesans wore an embroidered overgarment above the kimono (Uchikake). This can be seen in art, especially in the representations of the women walking down the main street of the pleasure quarter on their way to the teahouse to receive a guest.

In the middle of the 18th century, portraits of the pleasure women appeared (Okubi-e: "large head"). Even though their features are more evident in these prints, the name of the courtesan appears at the top, and the emblem of her brothel on her clothing. Such pictures, in which the women appear as models of fashion, refinement and beauty, were publicity for the brothels. In the 1890s, the pinnacle of this art was achieved by Kitagawa Utamaro, who created a new feminine ideal. The figures were noble, elongated and restrained. Among his important works were portraits of courtesans and pleasure girls, sometimes on a glittering mica background.

In fact, of course, the prostitutes' existence was wretched, However, since the woodblock prints were censored, very few of the sketches for blocks (Hanshita) which were not authorized have survived. These drawings depict the bleak reality, and include prostitutes who have become pregnant and are made to undergo abortions or physical punishment, as seen in the sketches of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861).

In the Japanese aesthetic and erotica there is a distinct preference for hints or suggestions of possible or actual events which are never actually portrayed. Just as the buds of the cherry blossom are thought to be more beautiful than the flowers in full bloom, so eroticism in art does not actually show the sexual act, unlike the shunga prints (shunga: "art of spring"), but suggests what is about to happen, or what is happening but cannot be seen. The courtesans are usually clothed from neck to foot. The Japanese sensuality is expressed here in a sort of hide-and-seek peepshow. Some parts of the body are exposed, arousing erotic sensation. Ordinary women wore socks (tabi), but the courtesans walked barefoot, their feet whitened with a special powder, in high clogs, which could be as tall as 20 centimetres, covered with black lacquer.

In Katsushika Hokusai's (1760-1849) paintings, and in the prints of Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Ikeda Eisen (1790-1848), a white foot peeping from beneath a red kimono which is partly open is sensually suggestive. Other hints are the display of the inner side of the arm, the long, exposed nape of the neck, a strand of loose hair, and the red lips across the white complexion of the face. In such pictures, the courtesan is presented in tantalizing poses, holding a paper tissue or the corner of a headscarf in her mouth; or standing by a folding screen that conceals part of the room; lowering the flame of the lamp which stands near a pillow, with a tray nearby on which are two cups of sake or tea; sometimes items of male clothing or a tobacco pouch, suggesting that a client is with her, even if he does not appear in the picture. Even the woman holding or plucking the strings of a shamisen, as in the fan-print by Ando Hiroshige

(1797-1858), has connotations of erotica because of its associations with the pleasure quarter. These small details indicate that erotica was at least as important to the artist as the sexual act itself, and confirms that the sensuality conveyed by the courtesans was more important than anything else.

There are depictions of so many events in the pleasure quarter - such as the New Year celebrations, or the flowering of the cherry trees. The prints of Utagawa Kunimitsu (ca. 1801-1811) and Ando Hiroshige present the main street decorated with trees in full bloom on the third day of the third month, and the procession of the most beautiful courtesans. They parade together with their assistants who hold parasols to shade them, and carry a lantern or a chest with a fresh kimono if the courtesan is on her way to the teahouse to meet a client. In these pictures the courtesan is taller than her companions, and conspicuous by her elegance, with her attendants on either side of her, dressed in matching garments. The emblem of the brothel where she is employed appears on her clothing and on theirs. These parades, and the prints and paintings depicting them were intended to attract more visitors to the quarter. During the

18th century the parades became more and more extravagant, and the courtesans competed as to who would wear the most elaborate kimono, thus confirming their success with the wealthiest clients who could afford to bestow such luxuries on them.

In such scenes, the courtesan is something like a rock star or Hollywood idol, an ideal of womanhood, although she was really an erotic article. The processions moved slowly, so that visitors to the quarter could watch these embodiments of aesthetic sensuality. Journalists came to write guidebooks about the pleasure quarter and the courtesans, and respectable women came to see the show as if it were a fashion parade, while the artists certainly depicted it in this light.

The paintings also portray the lower-class prostitutes sitting behind the wooden bars of their pens on view for passersby. They are not, as might be assumed, naked, but wear kimonos, and are reading, or playing music, or engaged in other cultural activities. Sometimes a samurai can be seen crossing the street, wearing a straw hat for concealment, a pair of swords thrust into his sash so that a viewer can identify him, even though, in fact, they were obliged to leave their weapons at the gate of the quarter before entering.

Illegal prostitution, which was not penalized by the authorities as long as no disturbances were created, is also depicted in art. There is a portrayal, for instance, of streetwalkers (tsujikimi), also called Yotaka ("night hawk") perhaps, because they ‘hunted' clients there at night, like birds of prey. In Ando Hiroshige's triptych of scenes from the Kabuki, a prostitute and her customer can be seen in the left panel. She wears a headscarf as she walks along, and carries a straw mat. The customer is tugging at the mat, perhaps trying to persuade her to lie with him. The artists also depicted the girl attendants of the bath-house (Yuna) who were also prostitutes, and the women who entertained their customers on pleasure boats (Funa manju), as in the fan-print by Hiroshige. Just north of the Ryogoku Bridge, which was completed in Edo in 1661, one could hire a small boat to ply up the Sumida River and reach the pleasure quarter through the Japan Canal. At the anchorage underneath the bridge, as is clearly shown in Hiroshige's print, one could also hire pleasure boats (Yakatabune) and sail away, accompanied by pleasure girls, past the teahouses which lined the river bank.

Artists of the time also painted general views of the pleasure quarter and its occupants. In some of them a western influence is already evident in the use of perspective. These works are totally different from the classic Japanese style, the Yamato-e, in which the composition is different and perspective is inverted, creating a two-dimensionality, in which the buildings are without roofs so that the viewer can see what is going on in several rooms at once.

From pictures of the pleasure quarter we also learn that the artists viewed them in the same light as any other district of the city. Ando Hiroshige's series of prints, for instance, the "Ten famous views of Kyoto", included famous temples together with the entrance to the Shimabara pleasure quarter.

The courtesans were also portrayed with humour. In a print by Suzuki Haronobu, and in a painting by Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889), a courtesan is seen together with a figure of Daruma (the Buddhist monk Bodidharma), who founded Zen Buddhism in China. In Japanese, "Daruma" is a double entendre that also means "prostitute", thus hinting at the occupation of the pretty girl. Sometimes a courtesan is shown flying on the back of a crane. Suzuki Haronobu's print on this subject is simply a parody of the Chinese sage depicted in art riding on a crane, the symbol of longevity. Equating a courtesan with a Chinese sage is obviously a humorous suggestion that the courtesan is as versed in the classical arts as the Chinese sages.

At the end of the Edo era, synthetic colours were imported from Europe for use in paintings and prints, and the ukiyo-e prints lost the elegance and refinement achieved by use of natural colours. They became more dominant, exaggerated. The traditions of the Beijin-ga prints were carried on by pupils of the Utagawa School, and those of Ando Hiroshige. In the present exhibition there are works by Tsukiyoka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) and Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900).

The great artists of Japan depicted the pleasure quarter and its women, emphasizing their unique place in Japanese society of the time. The ukiyo-e paintings presented all this in a free, colourful fashion, emphasizing the decorative aspect. When the trend turned from painting to the woodblock print, quite a few renowned artists created prints in the ukiyo-e spirit. From the early monochrome prints of the end of the 17th century, which were coloured by hand, to the first coloured prints (nishiki-e) by Suzuki Haronobu, which appeared in ca.1764, in which each colour was printed from a separate block, it is obvious that the Japanese artists devoted all their talents to depicting this fascinating subject.